연구 설계(Research Designs)

연구 설계

By Christie Napa ScollonSingapore Management University

Psychologists test research questions using a variety of methods. Most research relies on either correlations or experiments. With correlations, researchers measure variables as they naturally occur in people and compute the degree to which two variables go together. With experiments, researchers actively make changes in one variable and watch for changes in another variable. Experiments allow researchers to make causal inferences. Other types of methods include longitudinal and quasi-experimental designs. Many factors, including practical constraints, determine the type of methods researchers use. Often researchers survey people even though it would be better, but more expensive and time consuming, to track them longitudinally.

심리학자들은 다양한 방법으로 연구 질문을 테스트합니다. 대부분의 연구는 상관관계 또는 실험에 의존합니다. 상관관계를 통해 연구자들은 사람들에게서 자연적으로 발생하는 변수를 측정하고 두 변수가 서로 어느 정도 연관되어 있는지를 계산합니다. 실험을 통해 연구자는 한 변수를 적극적으로 변경하고 다른 변수의 변화를 관찰합니다. 실험을 통해 연구자는 인과관계를 추론할 수 있습니다. 다른 유형의 방법으로는 종단 및 준실험 설계가 있습니다. 연구자가 사용하는 방법의 유형은 현실적인 제약을 포함한 여러 요인에 따라 결정됩니다. 비용과 시간을 들여 사람들을 종단적으로 추적하는 것이 더 좋긴 하지만 연구자들은 설문조사를 실시할 때도 있습니다.

학습 목표(Learning Objectives)

- Articulate the difference between correlational and experimental designs.

- Understand how to interpret correlations.

- Understand how experiments help us to infer causality.

- Understand how surveys relate to correlational and experimental research.

- Explain what a longitudinal study is.

- List a strength and weakness of different research designs.

- 상관법과 실험 설계의 차이점을 명확하게 설명합니다.

- 상관 관계를 어떻게 해석하는지 이해합니다.

- 실험이 인과 관계를 유추하는 데 어떻게 도움을 주는지 이해합니다.

- 설문 조사가 상관관계 연구와 실험 연구에 어떻게 관련되 있는지 이해합니다.

- 종단 연구가 무엇인지 설명합니다.

- 서로 다른 연구 설계의 강점과 약점을 나열합니다.

연구 설계

In the early 1970’s, a man named Uri Geller tricked the world: he convinced hundreds of thousands of people that he could bend spoons and slow watches using only the power of his mind. In fact, if you were in the audience, you would have likely believed he had psychic powers. Everything looked authentic—this man had to have paranormal abilities! So, why have you probably never heard of him before? Because when Uri was asked to perform his miracles in line with scientific experimentation, he was no longer able to do them. That is, even though it seemed like he was doing the impossible, when he was tested by science, he proved to be nothing more than a clever magician.

1970년대 초, 우리 겔러라는 남자는 마음의 힘만으로 숟가락을 구부리고 시계를 늦출 수 있다고 수십만 명의 사람들을 속여 세상을 놀라게 했습니다. 사실, 당신이 그 자리에 있었다면 그가 초능력을 가지고 있다고 믿었을 것입니다. 모든 것이 진짜처럼 보였으니 초자연적인 능력을 가진 사람임에 틀림없었죠! 그렇다면 왜 여러분은 그에 대해 들어본 적이 없었을까요? 과학적 실험에 따라 기적을 행하라는 요청을 받았을 때 우리는 더 이상 기적을 행할 수 없었기 때문입니다. 즉, 불가능한 일을 하는 것처럼 보였지만 과학적 실험을 해보니 영리한 마술사에 지나지 않았다는 사실이 밝혀졌습니다.

When we look at dinosaur bones to make educated guesses about extinct life, or systematically chart the heavens to learn about the relationships between stars and planets, or study magicians to figure out how they perform their tricks, we are forming observations—the foundation of science. Although we are all familiar with the saying “seeing is believing,” conducting science is more than just what your eyes perceive. Science is the result of systematic and intentional study of the natural world. And psychology is no different. In the movie Jerry Maguire, Cuba Gooding, Jr. became famous for using the phrase, “Show me the money!” In psychology, as in all sciences, we might say, “Show me the data!”

공룡 뼈를 보고 멸종된 생명체에 대해 추측하거나, 별과 행성의 관계를 알아보기 위해 체계적으로 하늘을 도표로 만들거나, 마술사의 마술 수행 방법을 알아내기 위해 연구할 때, 우리는 과학의 기초인 관찰을 하고 있습니다. '백문이 불여일견'이라는 말에 익숙하지만, 과학을 수행한다는 것은 단순히 눈으로 인식하는 것 그 이상입니다. 과학은 자연계에 대한 체계적이고 의도적인 연구의 결과물입니다. 심리학도 다르지 않습니다. 영화 'Jerry Maguire'에서 쿠바 구딩 주니어는 "Show me the money!"라는 대사로 유명해졌습니다. 모든 과학이 그렇듯이 심리학에서도 "데이터를 보여주세요!"라고 말할 수 있습니다.

One of the important steps in scientific inquiry is to test our research questions, otherwise known as hypotheses. However, there are many ways to test hypotheses in psychological research. Which method you choose will depend on the type of questions you are asking, as well as what resources are available to you. All methods have limitations, which is why the best research uses a variety of methods.

과학적 탐구에서 중요한 단계 중 하나는 가설이라고도 하는 연구 질문을 검증하는 것입니다. 하지만 심리학 연구에서 가설을 검증하는 방법에는 여러 가지가 있습니다. 어떤 방법을 선택할지는 질문의 유형과 사용 가능한 리소스에 따라 달라집니다. 모든 방법에는 한계가 있기 때문에 최고의 연구는 다양한 방법을 사용합니다.

Most psychological research can be divided into two types: experimental and correlational research.

대부분의 심리학 연구는 실험 연구와 상관관계 연구의 두 가지 유형으로 나눌 수 있습니다.

실험 연구

If somebody gave you $20 that absolutely had to be spent today, how would you choose to spend it? Would you spend it on an item you’ve been eyeing for weeks, or would you donate the money to charity? Which option do you think would bring you the most happiness? If you’re like most people, you’d choose to spend the money on yourself (duh, right?). Our intuition is that we’d be happier if we spent the money on ourselves.

누군가 오늘 당장 써야 하는 20달러를 준다면 어떻게 사용하시겠습니까? 몇 주 동안 눈여겨보던 물건에 쓰시겠습니까, 아니면 자선단체에 기부하시겠습니까? 어떤 선택이 여러분에게 가장 큰 행복을 가져다줄 것이라고 생각하시나요? 대부분의 사람들이 그렇듯이 여러분도 자신을 위해 돈을 쓰는 것을 선택하실 것입니다. 돈을 자신을 위해 쓰면 더 행복할 것 같다는 직감이 들기 때문입니다.

Knowing that our intuition can sometimes be wrong, Professor Elizabeth Dunn (2008) at the University of British Columbia set out to conduct an experiment on spending and happiness. She gave each of the participants in her experiment $20 and then told them they had to spend the money by the end of the day. Some of the participants were told they must spend the money on themselves. Some students were told they must spend the money on others, such as a charity or a gift for someone. At the end of the day she measured participants’ levels of happiness using a self-report questionnaire. (But wait, how do you measure something like happiness when you can’t really see it? Psychologists measure many abstract concepts, such as happiness and intelligence, by beginning with operational definitions of the concepts. See the Noba modules on Intelligence [http://noba.to/ncb2h79v] and Happiness [http://noba.to/qnw7g32t], respectively, for more information on specific measurement strategies.)

브리티시 컬럼비아 대학교의 엘리자베스 던 교수(2008)는 직관이 때때로 틀릴 수 있다는 사실을 알고 지출과 행복에 관한 실험을 시작했습니다. 던 교수는 실험 참가자들에게 각각 20달러를 준 다음 하루가 끝날 때까지 돈을 써야 한다고 말했습니다. 일부 참가자에게는 돈을 자신을 위해 써야 한다고 말했습니다. 일부 학생들은 자선 단체나 누군가를 위한 선물 등 다른 사람을 위해 돈을 써야 한다고 들었습니다. 하루가 끝나면 자기보고식 설문지를 사용하여 참가자들의 행복 수준을 측정했습니다. (하지만 잠깐만요, 행복과 같은 것을 실제로 볼 수 없는데 어떻게 측정할 수 있을까요? 심리학자들은 행복이나 지능과 같은 추상적인 개념을 측정할 때 개념에 대한 조작적 정의부터 시작합니다. 구체적인 측정 전략에 대한 자세한 내용은 각각 지능[http://noba.to/ncb2h79v] 및 행복[http://noba.to/qnw7g32t]에 대한 Noba 모듈을 참조하세요.)

In an experiment, researchers manipulate, or cause changes, in the independent variable, and observe or measure any impact of those changes in the dependent variable. The independent variable is the one under the experimenter’s control, or the variable that is intentionally altered between groups. In the case of Dunn’s experiment, the independent variable was whether participants spent the money on themselves or on others. The dependent variable is the variable that is not manipulated at all, or the one where the effect happens. One way to help remember this is that the dependent variable “depends” on what happens to the independent variable. In our example, the participants’ happiness (the dependent variable in this experiment) depends on how the participants spend their money (the independent variable). Thus, any observed changes or group differences in happiness can be attributed to whom the money was spent on. What Dunn and her colleagues found was that, after all the spending had been done, the people who had spent the money on others were happier than those who had spent the money on themselves. In other words, spending on others causes us to be happier than spending on ourselves. Do you find this surprising?

실험에서 연구자는 독립 변수를 조작하거나 변화를 일으키고, 이러한 변화가 종속 변수에 미치는 영향을 관찰하거나 측정합니다. 독립 변수는 실험자가 통제할 수 있는 변수 또는 그룹 간에 의도적으로 변경되는 변수입니다. 던의 실험에서 독립 변수는 참가자가 돈을 자신을 위해 사용했는지, 아니면 다른 사람을 위해 사용했는지 여부였습니다. 종속 변수는 전혀 조작되지 않은 변수 또는 효과가 발생하는 변수입니다. 이를 기억하는 데 도움이 되는 한 가지 방법은 종속 변수가 독립 변수에 어떤 일이 일어나는지에 "의존"한다는 것입니다. 이 예에서 참가자의 행복도(이 실험의 종속 변수)는 참가자가 돈을 어떻게 쓰는지(독립 변수)에 따라 달라집니다. 따라서 관찰된 변화나 행복도의 그룹 간 차이는 돈을 누구에게 썼는지에 따라 달라질 수 있습니다. 던과 그녀의 동료들이 발견한 것은 모든 지출이 이루어진 후, 다른 사람에게 돈을 쓴 사람들이 자신을 위해 돈을 쓴 사람들보다 더 행복하다는 것이었습니다. 다시 말해, 타인을 위해 지출하면 자신을 위해 지출하는 것보다 더 행복해집니다. 이 결과가 놀랍지 않나요?

But wait! Doesn’t happiness depend on a lot of different factors—for instance, a person’s upbringing or life circumstances? What if some people had happy childhoods and that’s why they’re happier? Or what if some people dropped their toast that morning and it fell jam-side down and ruined their whole day? It is correct to recognize that these factors and many more can easily affect a person’s level of happiness. So how can we accurately conclude that spending money on others causes happiness, as in the case of Dunn’s experiment?

하지만 잠깐만요! 행복은 개인의 성장 환경이나 생활 환경 등 다양한 요인에 따라 달라지지 않을까요? 어떤 사람들은 행복한 어린 시절을 보냈기 때문에 더 행복하다면 어떨까요? 또는 어떤 사람은 아침에 토스트를 떨어뜨려서 토스트가 뒤집혀서 하루 종일 망쳤다면 어떨까요? 이러한 요인들과 더 많은 요인들이 사람의 행복 수준에 쉽게 영향을 미칠 수 있다는 것을 인식하는 것이 옳습니다. 그렇다면 던의 실험에서처럼 다른 사람을 위해 돈을 쓰는 것이 행복을 가져온다고 어떻게 정확하게 결론을 내릴 수 있을까요?

The most important thing about experiments is random assignment. Participants don’t get to pick which condition they are in (e.g., participants didn’t choose whether they were supposed to spend the money on themselves versus others). The experimenter assigns them to a particular condition based on the flip of a coin or the roll of a die or any other random method. Why do researchers do this? With Dunn’s study, there is the obvious reason: you can imagine which condition most people would choose to be in, if given the choice. But another equally important reason is that random assignment makes it so the groups, on average, are similar on all characteristics except what the experimenter manipulates.

실험에서 가장 중요한 것은 무작위 배정입니다. 참가자는 자신이 어떤 조건에 놓일지 선택할 수 없습니다(예: 참가자가 돈을 자신에게 쓸지 다른 사람에게 쓸지 선택하지 않음). 실험자는 동전 던지기, 주사위 굴리기 또는 기타 무작위적인 방법을 통해 참가자를 특정 조건에 배정합니다. 연구자들은 왜 이렇게 할까요? 던의 연구에는 분명한 이유가 있습니다. 선택권이 주어진다면 대부분의 사람들이 어떤 조건을 선택할지 상상할 수 있기 때문입니다. 그러나 또 다른 중요한 이유는 무작위 배정을 통해 실험자가 조작한 것을 제외한 모든 특성에서 평균적으로 그룹이 비슷해지기 때문입니다.

By randomly assigning people to conditions (self-spending versus other-spending), some people with happy childhoods should end up in each condition. Likewise, some people who had dropped their toast that morning (or experienced some other disappointment) should end up in each condition. As a result, the distribution of all these factors will generally be consistent across the two groups, and this means that on average the two groups will be relatively equivalent on all these factors. Random assignment is critical to experimentation because if the only difference between the two groups is the independent variable, we can infer that the independent variable is the cause of any observable difference (e.g., in the amount of happiness they feel at the end of the day).

사람들을 무작위로 조건(자신을 위한 소비와 타인을 위한 소비)에 할당하면 어린 시절이 행복했던 사람들이 각 조건에 속하게 될 것입니다. 마찬가지로, 그날 아침 토스트를 떨어뜨렸거나 다른 실망스러운 경험을 한 사람들도 각 조건에 속하게 될 것입니다. 결과적으로 이러한 모든 요인의 분포는 일반적으로 두 그룹에 걸쳐 일관되며, 이는 평균적으로 두 그룹이 이러한 모든 요인에 대해 상대적으로 동등하다는 것을 의미합니다. 두 그룹 간의 유일한 차이가 독립 변수인 경우, 독립 변수가 관찰 가능한 차이(예: 하루가 끝날 때 느끼는 행복감)의 원인이라고 추론할 수 있기 때문에 무작위 할당은 실험에 매우 중요합니다.

Here’s another example of the importance of random assignment: Let’s say your class is going to form two basketball teams, and you get to be the captain of one team. The class is to be divided evenly between the two teams. If you get to pick the players for your team first, whom will you pick? You’ll probably pick the tallest members of the class or the most athletic. You probably won’t pick the short, uncoordinated people, unless there are no other options. As a result, your team will be taller and more athletic than the other team. But what if we want the teams to be fair? How can we do this when we have people of varying height and ability? All we have to do is randomly assign players to the two teams. Most likely, some tall and some short people will end up on your team, and some tall and some short people will end up on the other team. The average height of the teams will be approximately the same. That is the power of random assignment!

다음은 무작위 배정의 중요성을 보여주는 또 다른 예입니다: 학급에서 두 개의 농구 팀을 구성하고 한 팀의 주장을 맡게 되었다고 가정해 보겠습니다. 학급은 두 팀으로 균등하게 나뉘어야 합니다. 팀의 선수를 먼저 뽑을 수 있다면 누구를 뽑으시겠습니까? 아마도 반에서 키가 가장 크거나 운동 능력이 가장 뛰어난 학생을 뽑을 것입니다. 다른 선택지가 없는 한 키가 작고 협동심이 없는 사람은 뽑지 않을 것입니다. 결과적으로 여러분의 팀은 다른 팀보다 키가 크고 운동량이 많은 팀이 될 것입니다. 하지만 팀을 공정하게 구성하려면 어떻게 해야 할까요? 다양한 키와 능력을 가진 사람들이 있을 때 어떻게 하면 공평하게 할 수 있을까요? 두 팀에 무작위로 선수를 배정하기만 하면 됩니다. 대부분 키가 큰 사람과 키가 작은 사람이 한 팀에 속하게 되고, 키가 큰 사람과 키가 작은 사람이 다른 팀에 속하게 될 것입니다. 두 팀의 평균 키는 거의 같을 것입니다. 이것이 바로 무작위 배정의 힘입니다!

기타 고려 사항

In addition to using random assignment, you should avoid introducing confounds into your experiments. Confounds are things that could undermine your ability to draw causal inferences. For example, if you wanted to test if a new happy pill will make people happier, you could randomly assign participants to take the happy pill or not (the independent variable) and compare these two groups on their self-reported happiness (the dependent variable). However, if some participants know they are getting the happy pill, they might develop expectations that influence their self-reported happiness. This is sometimes known as a placebo effect. Sometimes a person just knowing that he or she is receiving special treatment or something new is enough to actually cause changes in behavior or perception: In other words, even if the participants in the happy pill condition were to report being happier, we wouldn’t know if the pill was actually making them happier or if it was the placebo effect—an example of a confound. A related idea is participant demand. This occurs when participants try to behave in a way they think the experimenter wants them to behave. Placebo effects and participant demand often occur unintentionally. Even experimenter expectations can influence the outcome of a study. For example, if the experimenter knows who took the happy pill and who did not, and the dependent variable is the experimenter’s observations of people’s happiness, then the experimenter might perceive improvements in the happy pill group that are not really there.

무작위 할당을 사용하는 것 외에도 실험에 혼동을 유발하는 요소를 피해야 합니다. 혼란은 인과 관계를 추론하는 능력을 약화시킬 수 있는 요소입니다. 예를 들어, 새로운 행복 약이 사람들을 더 행복하게 만드는지 테스트하려는 경우, 참가자를 무작위로 행복 약 복용 여부(독립 변수)에 따라 배정하고 두 그룹의 자가 보고 행복도(종속 변수)를 비교할 수 있습니다. 그러나 일부 참가자가 행복 약을 복용한다는 사실을 알고 있다면, 자기 보고 행복도에 영향을 미치는 기대감을 갖게 될 수 있습니다. 이를 위약 효과라고도 합니다. 때로는 자신이 특별한 대우를 받고 있거나 새로운 것을 받고 있다는 사실만으로도 행동이나 인식에 변화를 일으킬 수 있습니다: 즉, 행복 약을 먹은 참가자가 더 행복해졌다고 보고하더라도 실제로 행복 약이 먹은 참가자를 더 행복하게 만든 것인지 아니면 위약 효과(혼동의 예)인지는 알 수 없습니다. 이와 비슷하게 참가자 요구( participant demand)라는 개념이 있습니다. 이는 실험 참가자가 실험자가 원하는 방식으로 행동하려고 할 때 발생합니다. 위약 효과와 참가자 요구는 의도치 않게 발생하는 경우가 많습니다. 실험자의 기대조차도 연구 결과에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 실험자가 행복 약을 복용한 사람과 복용하지 않은 사람을 알고 있고 종속 변수가 사람들의 행복에 대한 실험자의 관찰인 경우, 실험자는 행복 약을 복용한 그룹에서 실제로는 존재하지 않는 개선이 있었다고 인식할 수 있습니다.

One way to prevent these confounds from affecting the results of a study is to use a double-blind procedure. In a double-blind procedure, neither the participant nor the experimenter knows which condition the participant is in. For example, when participants are given the happy pill or the fake pill, they don’t know which one they are receiving. This way, the participants are less likely to be influenced by any researcher expectations (called "participant demand"). Likewise, the researcher doesn’t know which pill each participant is taking (at least in the beginning—later, the researcher will get the results for data-analysis purposes), which means the researcher’s expectations can’t influence his or her observations. Therefore, because both parties are “blind” to the condition, neither will be able to behave in a way that introduces a confound. At the end of the day, the only difference between groups will be which pills the participants received, allowing the researcher to determine if the happy pill actually caused people to be happier.

이러한 혼동이 연구 결과에 영향을 미치는 것을 방지하는 한 가지 방법은 이중 맹검 절차를 사용하는 것입니다. 이중맹검 절차에서는 참가자나 실험자 모두 참가자가 어떤 상태에 있는지 알지 못합니다. 예를 들어, 참가자에게 행복 약과 가짜 약이 주어졌을 때 참가자는 어떤 알약을 받고 있는지 알 수 없습니다. 이렇게 하면 참가자는 연구자의 기대(참가자 요구)에 영향을 받을 가능성이 줄어듭니다. 마찬가지로, 연구자는 각 참가자가 어떤 약을 복용하고 있는지 알 수 없으므로(최소한 처음에는, 나중에는 데이터 분석 목적으로 결과를 얻어야 함) 연구자의 기대가 관찰에 영향을 미칠 수 없습니다. 따라서 두 당사자 모두 어떤 조건인지 모르기 때문에 어느 쪽도 혼돈을 야기하는 방식으로 행동할 수 없습니다. 결국 그룹 간의 유일한 차이점은 참가자가 어떤 약을 받았는지이므로 연구자는 행복 약이 실제로 사람들을 더 행복하게 만들었는지 확인할 수 있습니다.

상관 설계

When scientists passively observe and measure phenomena it is called correlational research. Here, we do not intervene and change behavior, as we do in experiments. In correlational research, we identify patterns of relationships, but we usually cannot infer what causes what. Importantly, with correlational research, you can examine only two variables at a time, no more and no less.

과학자가 수동적으로 현상을 관찰하고 측정하는 것을 상관 연구라고 합니다. 여기서는 실험에서처럼 개입하여 행동을 변화시키지 않습니다. 상관 연구에서는 관계의 패턴을 파악하지만, 일반적으로 무엇이 무엇의 원인인지 추론할 수는 없습니다. 중요한 것은 상관관계 연구에서는 한 번에 두 가지 변수만 조사할 수 있다는 것입니다.

So, what if you wanted to test whether spending on others is related to happiness, but you don’t have $20 to give to each participant? You could use a correlational design—which is exactly what Professor Dunn did, too. She asked people how much of their income they spent on others or donated to charity, and later she asked them how happy they were. Do you think these two variables were related? Yes, they were! The more money people reported spending on others, the happier they were.

다른 사람을 위한 지출이 행복과 관련이 있는지 테스트하고 싶지만 각 참가자에게 20달러를 줄 수 없다면 어떻게 해야 할까요? Dunn 교수가 사용한 것과 같은 상관 관계 설계를 사용할 수 있습니다. 던 교수는 사람들에게 수입의 얼마를 다른 사람을 위해 쓰거나 자선단체에 기부하는지 물은 다음, 얼마나 행복한지 물었습니다. 이 두 변수가 서로 관련이 있다고 생각하시나요? 네, 상관관계가 있었습니다! 다른 사람을 위해 더 많은 돈을 지출한다고 답한 사람일수록 더 행복하다고 답했습니다.

상관관게에 대한 더 많은 디테일

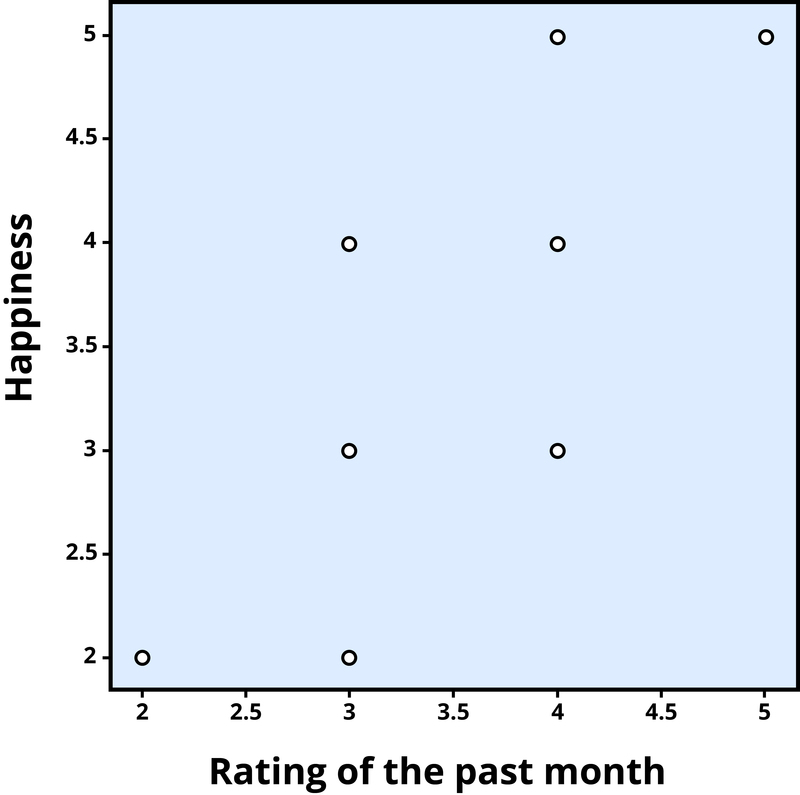

To find out how well two variables correspond, we can plot the relation between the two scores on what is known as a scatterplot (Figure 1). In the scatterplot, each dot represents a data point. (In this case it’s individuals, but it could be some other unit.) Importantly, each dot provides us with two pieces of information—in this case, information about how good the person rated the past month (x-axis) and how happy the person felt in the past month (y-axis). Which variable is plotted on which axis does not matter.

두 변수가 얼마나 잘 일치하는지 알아보기 위해 두 점수 간의 관계를 산점도로 표시할 수 있습니다(그림 1). 분산형 차트에서 각 점은 데이터 포인트를 나타냅니다. (이 경우 개인이지만 다른 단위일 수도 있습니다.) 중요한 것은 각 점이 두 가지 정보, 즉 이 경우 지난 달에 그 사람이 얼마나 좋은 평가를 받았는지(X축)와 지난 달에 그 사람이 얼마나 행복하다고 느꼈는지(Y축)에 대한 정보를 제공한다는 점입니다. 어떤 변수가 어느 축에 표시되는지는 중요하지 않습니다.

The association between two variables can be summarized statistically using the correlation coefficient (abbreviated as r). A correlation coefficient provides information about the direction and strength of the association between two variables. For the example above, the direction of the association is positive. This means that people who perceived the past month as being good reported feeling more happy, whereas people who perceived the month as being bad reported feeling less happy.

두 변수 간의 연관성은 상관계수(약칭: r)를 사용하여 통계적으로 요약할 수 있습니다. 상관 계수는 두 변수 간의 연관성의 방향과 강도에 대한 정보를 제공합니다. 위의 예에서 연관성의 방향은 양수입니다. 즉, 지난 달이 좋았다고 인식한 사람들은 행복감을 더 많이 느낀 반면, 나빴다고 인식한 사람들은 행복감을 덜 느꼈다고 보고했습니다.

With a positive correlation, the two variables go up or down together. In a scatterplot, the dots form a pattern that extends from the bottom left to the upper right (just as they do in Figure 1). The r value for a positive correlation is indicated by a positive number (although, the positive sign is usually omitted). Here, the r value is .81.

양의 상관관계가 있으면 두 변수가 함께 상승하거나 하락합니다. 산점도에서 점은 그림 1에서와 같이 왼쪽 하단에서 오른쪽 상단으로 확장되는 패턴을 형성합니다. 양의 상관관계에 대한 r 값은 양수로 표시됩니다(양수 부호는 일반적으로 생략됨). 여기서 r 값은 .81입니다.

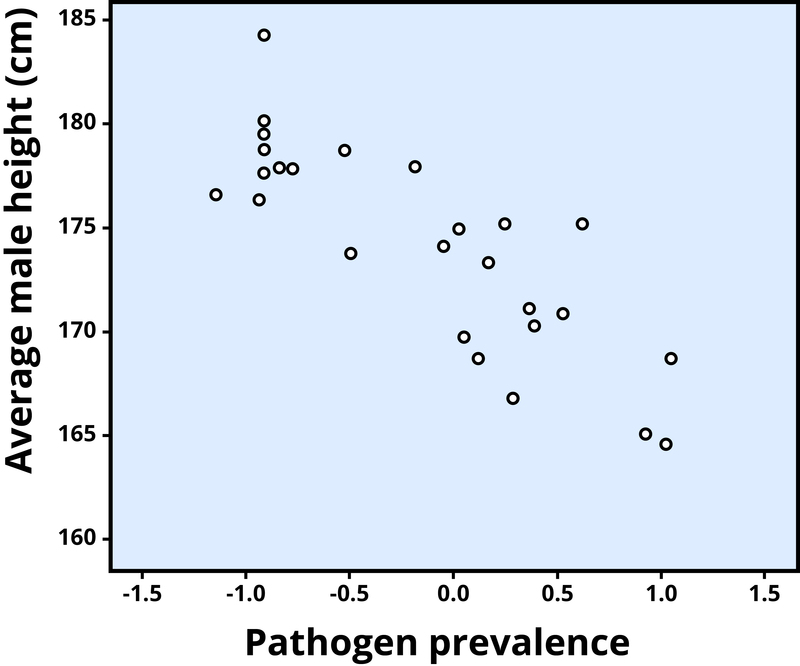

A negative correlation is one in which the two variables move in opposite directions. That is, as one variable goes up, the other goes down. Figure 2 shows the association between the average height of males in a country (y-axis) and the pathogen prevalence (or commonness of disease; x-axis) of that country. In this scatterplot, each dot represents a country. Notice how the dots extend from the top left to the bottom right. What does this mean in real-world terms? It means that people are shorter in parts of the world where there is more disease. The r value for a negative correlation is indicated by a negative number—that is, it has a minus (–) sign in front of it. Here, it is –.83.

음의 상관관계는 두 변수가 서로 반대 방향으로 움직이는 상관관계입니다. 즉, 한 변수가 증가하면 다른 변수는 감소합니다. 그림 2는 한 국가의 남성 평균 키(y축)와 해당 국가의 병원체 유병률(또는 질병의 흔함, x축) 사이의 연관성을 보여줍니다. 이 산점도에서 각 점은 국가를 나타냅니다. 점이 왼쪽 상단에서 오른쪽 하단으로 확장되는 것을 볼 수 있습니다. 이것은 실제 세계에서 무엇을 의미할까요? 이는 질병이 더 많은 지역에서 사람들의 키가 더 작다는 것을 의미합니다. 음의 상관관계에 대한 r 값은 음수, 즉 그 앞에 마이너스(-) 기호가 있는 숫자로 표시됩니다. 여기서는 -.83입니다.

The strength of a correlation has to do with how well the two variables align. Recall that in Professor Dunn’s correlational study, spending on others positively correlated with happiness: The more money people reported spending on others, the happier they reported to be. At this point you may be thinking to yourself, I know a very generous person who gave away lots of money to other people but is miserable! Or maybe you know of a very stingy person who is happy as can be. Yes, there might be exceptions. If an association has many exceptions, it is considered a weak correlation. If an association has few or no exceptions, it is considered a strong correlation. A strong correlation is one in which the two variables always, or almost always, go together. In the example of happiness and how good the month has been, the association is strong. The stronger a correlation is, the tighter the dots in the scatterplot will be arranged along a sloped line.

상관관계의 강도는 두 변수가 얼마나 잘 일치하는가와 관련이 있습니다. 던 교수의 상관관계 연구에서 타인에 대한 지출은 행복과 양의 상관관계가 있었습니다: 타인에게 더 많은 돈을 지출한다고 응답한 사람일수록 더 행복하다고 응답했습니다. 이쯤 되면 여러분은 다른 사람에게 많은 돈을 기부하지만 불행한 사람을 알고 있다고 생각할지도 모릅니다! 아니면 아주 인색하지만 행복하게 사는 사람을 알고 있을 수도 있습니다. 네, 예외가 있을 수 있습니다. 연관성에 예외가 많으면 약한 상관관계로 간주합니다. 연관성에 예외가 거의 또는 전혀 없는 경우 강한 상관관계로 간주됩니다. 강한 상관관계는 두 변수가 항상 또는 거의 항상 함께 가는 상관관계입니다. 행복도와 이번 달이 얼마나 좋았는지의 예에서는 연관성이 강합니다. 상관 관계가 강할수록 분산형 차트의 점들이 경사진 선을 따라 더 촘촘하게 배열됩니다.

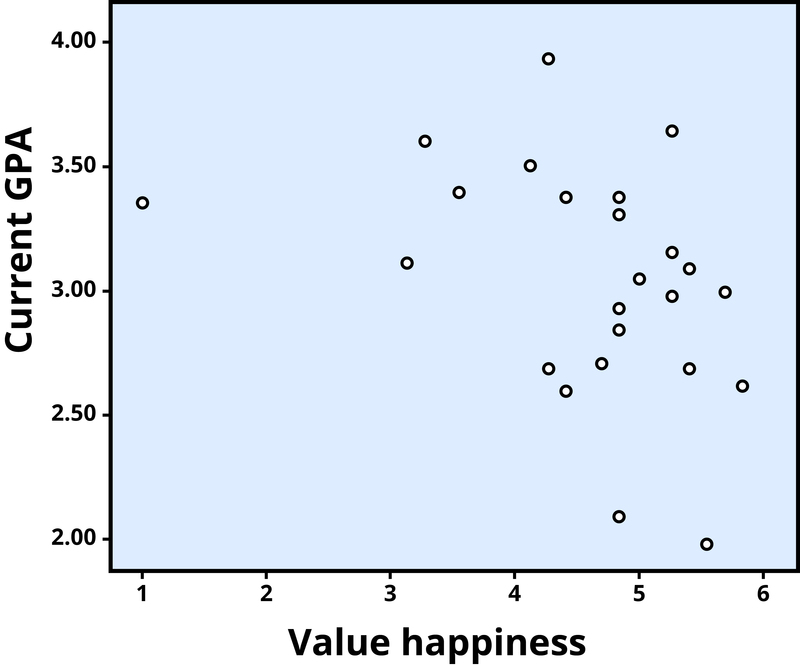

The r value of a strong correlation will have a high absolute value. In other words, you disregard whether there is a negative sign in front of the r value, and just consider the size of the numerical value itself. If the absolute value is large, it is a strong correlation. A weak correlation is one in which the two variables correspond some of the time, but not most of the time. Figure 3 shows the relation between valuing happiness and grade point average (GPA). People who valued happiness more tended to earn slightly lower grades, but there were lots of exceptions to this. The r value for a weak correlation will have a low absolute value. If two variables are so weakly related as to be unrelated, we say they are uncorrelated, and the r value will be zero or very close to zero. In the previous example, is the correlation between height and pathogen prevalence strong? Compared to Figure 3, the dots in Figure 2 are tighter and less dispersed. The absolute value of –.83 is large. Therefore, it is a strong negative correlation.

강한 상관관계의 r 값은 높은 절대값을 가집니다. 즉, r 값 앞에 음의 부호가 있는지 여부는 무시하고 숫자 값 자체의 크기만 고려합니다. 절대값이 크면 강한 상관관계입니다. 약한 상관관계는 두 변수가 일부 일치하지만 대부분의 경우 일치하지 않는 상관관계입니다. 그림 3은 행복을 중시하는 정도와 학점 평균(GPA)의 관계를 보여줍니다. 행복을 더 중요하게 생각하는 사람들은 약간 낮은 성적을 받는 경향이 있었지만, 여기에는 많은 예외가 있었습니다. 상관관계가 약한 경우의 R 값은 절대값이 낮습니다. 두 변수가 서로 관련이 없을 정도로 약한 상관관계가 있는 경우 상관관계가 없다고 말하며, r 값은 0이거나 0에 매우 가깝습니다. 앞의 예에서 키와 병원체 유병률 간의 상관관계는 강한가요? 그림 3과 비교하면 그림 2의 점들이 더 촘촘하고 분산이 덜 되어 있습니다. 절대값이 -.83으로 큽니다. 따라서 강한 음의 상관관계입니다.

Translated with DeepL

Can you guess the strength and direction of the correlation between age and year of birth? If you said this is a strong negative correlation, you are correct! Older people always have lower years of birth than younger people (e.g., 1950 vs. 1995), but at the same time, the older people will have a higher age (e.g., 65 vs. 20). In fact, this is a perfect correlation because there are no exceptions to this pattern. I challenge you to find a 10-year-old born before 2003! You can’t.

나이와 출생연도 사이의 상관관계의 강도와 방향을 짐작할 수 있나요? 강한 음의 상관관계라고 말씀하셨다면 정답입니다! 나이가 많은 사람은 항상 젊은 사람보다 출생 연도가 낮지만(예: 1950년 대 1995년), 동시에 나이가 많은 사람은 나이가 더 높습니다(예: 65세 대 20세). 사실, 이 패턴에는 예외가 없기 때문에 이것은 완벽한 상관관계입니다. 2003년 이전에 태어난 10세 어린이를 찾아보세요! 그럴 수 없습니다.

상관 관계의 문제

If generosity and happiness are positively correlated, should we conclude that being generous causes happiness? Similarly, if height and pathogen prevalence are negatively correlated, should we conclude that disease causes shortness? From a correlation alone, we can’t be certain. For example, in the first case it may be that happiness causes generosity, or that generosity causes happiness. Or, a third variable might cause both happiness and generosity, creating the illusion of a direct link between the two. For example, wealth could be the third variable that causes both greater happiness and greater generosity. This is why correlation does not mean causation—an often repeated phrase among psychologists.

관대함과 행복이 양의 상관관계가 있다면, 관대함이 행복을 유발한다고 결론을 내려야 할까요? 마찬가지로 키와 병원균 유병률이 음의 상관관계를 보인다면 질병이 키가 작아지는 원인이라고 결론을 내려야 할까요? 상관관계만으로는 확신할 수 없습니다. 예를 들어, 첫 번째 경우에는 행복이 관대함을 유발하거나 관대함이 행복을 유발할 수 있습니다. 또는 세 번째 변수가 행복과 관대함을 모두 유발하여 둘 사이에 직접적인 연관성이 있는 것처럼 착각하게 만들 수도 있습니다. 예를 들어, 부는 더 큰 행복과 더 큰 관대함을 모두 유발하는 세 번째 변수가 될 수 있습니다. 그렇기 때문에 심리학자들은 상관관계가 인과관계를 의미하지 않는다는 말을 자주 반복합니다.

질적 설계

Just as correlational research allows us to study topics we can’t experimentally manipulate (e.g., whether you have a large or small income), there are other types of research designs that allow us to investigate these harder-to-study topics. Qualitative designs, including participant observation, case studies, and narrative analysis are examples of such methodologies. Although something as simple as “observation” may seem like it would be a part of all research methods, participant observation is a distinct methodology that involves the researcher embedding him- or herself into a group in order to study its dynamics. For example, Festinger, Riecken, and Shacter (1956) were very interested in the psychology of a particular cult. However, this cult was very secretive and wouldn’t grant interviews to outside members. So, in order to study these people, Festinger and his colleagues pretended to be cult members, allowing them access to the behavior and psychology of the cult. Despite this example, it should be noted that the people being observed in a participant observation study usually know that the researcher is there to study them.

상관관계 연구를 통해 실험적으로 조작할 수 없는 주제(예: 소득이 많거나 적은지 여부)를 연구할 수 있는 것처럼, 연구하기 어려운 주제를 조사할 수 있는 다른 유형의 연구 디자인도 있습니다. 참가자 관찰, 사례 연구, 내러티브 분석을 포함한 질적 설계가 이러한 방법론의 예입니다. '관찰'같은 단순한 거라면 모든 연구 방법론에 들어가 있지 않냐고 할 수도 있지만, 참여자 관찰은 연구자가 그룹에 직접 들어가 그 역학을 연구하는 독특한 방법론입니다. 예를 들어, 페스팅거, 리켄, 샤터(1956)는 특정 종교 집단의 심리에 큰 관심을 가졌습니다. 그러나 이 종교 집단는 매우 비밀스러웠고 외부인과의 인터뷰를 허용하지 않았습니다. 그래서 페스팅거와 그의 동료들은 이 사람들을 연구하기 위해 그 종교 회원인 척하여 그 종교의 행동과 심리에 접근할 수 있었습니다. 이러한 예가 있음에도, 참가자 관찰 연구에서 관찰되는 사람들은 일반적으로 연구자가 자신을 연구하기 위해 그곳에 있다는 것을 알고 있다는 점을 주의해야 합니다.

Another qualitative method for research is the case study, which involves an intensive examination of specific individuals or specific contexts. Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, was famous for using this type of methodology; however, more current examples of case studies usually involve brain injuries. For instance, imagine that researchers want to know how a very specific brain injury affects people’s experience of happiness. Obviously, the researchers can’t conduct experimental research that involves inflicting this type of injury on people. At the same time, there are too few people who have this type of injury to conduct correlational research. In such an instance, the researcher may examine only one person with this brain injury, but in doing so, the researcher will put the participant through a very extensive round of tests. Hopefully what is learned from this one person can be applied to others; however, even with thorough tests, there is the chance that something unique about this individual (other than the brain injury) will affect his or her happiness. But with such a limited number of possible participants, a case study is really the only type of methodology suitable for researching this brain injury.

또 다른 질적 연구 방법으로는 특정 개인이나 특정 상황에 대한 집중적인 조사가 포함된 사례 연구가 있습니다. 정신분석학의 아버지인 지그문트 프로이트는 이러한 유형의 방법론을 사용한 것으로 유명하지만, 최근의 사례 연구 사례는 대개 뇌 손상에 관한 것입니다. 예를 들어, 연구자들이 매우 특정한 뇌 손상이 사람들의 행복 경험에 어떤 영향을 미치는지 알고 싶어한다고 가정해 봅시다. 물론 연구자들은 사람들에게 이런 종류의 부상을 입히는 실험 연구를 수행할 수 없습니다. 동시에 이러한 유형의 부상을 입은 사람의 수가 너무 적어 상관관계 연구를 수행할 수 없습니다. 이러한 경우 연구자는 이러한 뇌 손상을 입은 한 사람만 조사할 수 있지만, 이 경우 연구자는 참가자에게 매우 광범위한 테스트를 진행하게 됩니다. 이 한 사람에게서 배운 것을 다른 사람에게도 적용할 수 있기를 바라지만, 철저한 테스트를 거쳤더라도 뇌 손상 외에 이 개인의 고유한 특성이 행복에 영향을 미칠 가능성이 있습니다. 그러나 가능한 참가자 수가 제한되어 있기 때문에 사례 연구는 이 뇌 손상을 연구하는 데 적합한 유일한 방법론 유형입니다.

The final qualitative method to be discussed in this section is narrative analysis. Narrative analysis centers around the study of stories and personal accounts of people, groups, or cultures. In this methodology, rather than engaging with participants directly, or quantifying their responses or behaviors, researchers will analyze the themes, structure, and dialogue of each person’s narrative. That is, a researcher will examine people’s personal testimonies in order to learn more about the psychology of those individuals or groups. These stories may be written, audio-recorded, or video-recorded, and allow the researcher not only to study what the participant says but how he or she says it. Every person has a unique perspective on the world, and studying the way he or she conveys a story can provide insight into that perspective.

이 섹션에서 논의할 마지막 정성적 방법은 내러티브 분석입니다. 내러티브 분석은 사람, 집단 또는 문화에 대한 이야기와 개인적인 설명을 연구하는 데 중점을 둡니다. 이 방법론에서 연구자는 참여자와 직접 소통하거나 그들의 반응이나 행동을 정량화하는 대신 각 사람의 내러티브의 주제, 구조, 대화를 분석합니다. 즉, 연구자는 개인 또는 집단의 심리에 대해 자세히 알아보기 위해 사람들의 개인적인 증언을 조사합니다. 이러한 이야기는 서면, 음성 녹음 또는 비디오 녹화로 이루어질 수 있으며, 연구자는 참가자가 말하는 내용뿐만 아니라 말하는 방식도 연구할 수 있습니다. 모든 사람은 세상을 바라보는 고유한 관점을 가지고 있으며, 이야기를 전달하는 방식을 연구하면 그 관점에 대한 통찰력을 얻을 수 있습니다.

준실험 설계

What if you want to study the effects of marriage on a variable? For example, does marriage make people happier? Can you randomly assign some people to get married and others to remain single? Of course not. So how can you study these important variables? You can use a quasi-experimental design.

결혼이 어떤 변수에 미치는 영향을 연구하고 싶다면 어떻게 해야 할까요? 예를 들어, 결혼이 사람들을 더 행복하게 만들까요? 어떤 사람들은 결혼하고 어떤 사람들은 독신으로 남도록 무작위로 배정할 수 있을까요? 물론 불가능합니다. 그렇다면 이러한 중요한 변수를 어떻게 연구할 수 있을까요? 준실험 설계를 사용할 수 있습니다.

A quasi-experimental design is similar to experimental research, except that random assignment to conditions is not used. Instead, we rely on existing group memberships (e.g., married vs. single). We treat these as the independent variables, even though we don’t assign people to the conditions and don’t manipulate the variables. As a result, with quasi-experimental designs causal inference is more difficult. For example, married people might differ on a variety of characteristics from unmarried people. If we find that married participants are happier than single participants, it will be hard to say that marriage causes happiness, because the people who got married might have already been happier than the people who have remained single.

준실험 설계는 조건에 대한 무작위 할당을 사용하지 않는다는 점을 제외하면 실험 연구와 유사합니다. 대신, 기존에 있는 집단 풀(예: 기혼 대 미혼)을 활용합니다. 사람들을 조건에 할당하지 않고 변수를 조작하지 않더라도 이를 독립 변수로 취급합니다. 따라서 준실험 설계에서는 인과 관계를 추론하기가 더 어렵습니다. 예를 들어 기혼자는 미혼자와 다양한 특성에서 차이가 있을 수 있습니다. 기혼 참가자가 미혼 참가자보다 더 행복하다는 결과가 나온다면, 결혼한 사람들은 미혼으로 남아있는 사람들보다 이미 더 행복해 있었을 수 있기 때문에 결혼이 행복을 유발한다고 말하기는 어려울 것입니다.

Because experimental and quasi-experimental designs can seem pretty similar, let’s take another example to distinguish them. Imagine you want to know who is a better professor: Dr. Smith or Dr. Khan. To judge their ability, you’re going to look at their students’ final grades. Here, the independent variable is the professor (Dr. Smith vs. Dr. Khan) and the dependent variable is the students’ grades. In an experimental design, you would randomly assign students to one of the two professors and then compare the students’ final grades. However, in real life, researchers can’t randomly force students to take one professor over the other; instead, the researchers would just have to use the preexisting classes and study them as-is (quasi-experimental design). Again, the key difference is random assignment to the conditions of the independent variable. Although the quasi-experimental design (where the students choose which professor they want) may seem random, it’s most likely not. For example, maybe students heard Dr. Smith sets low expectations, so slackers prefer this class, whereas Dr. Khan sets higher expectations, so smarter students prefer that one. This now introduces a confounding variable (student intelligence) that will almost certainly have an effect on students’ final grades, regardless of how skilled the professor is. So, even though a quasi-experimental design is similar to an experimental design (i.e., both have independent and dependent variables), because there’s no random assignment, you can’t reasonably draw the same conclusions that you would with an experimental design.

실험 설계와 준실험 설계는 매우 비슷해 보일 수 있으므로 이를 구분하기 위해 다른 예를 들어 보겠습니다. 누가 더 나은 교수인지 알고 싶다고 가정해 보겠습니다: 스미스 박사와 칸 박사 중 누가 더 나은 교수인지 알고 싶다고 가정해 보겠습니다. 두 교수의 능력을 판단하기 위해 두 교수의 학생 최종 성적을 살펴볼 것입니다. 여기서 독립 변수는 교수(스미스 박사 대 칸 박사)이고 종속 변수는 학생의 성적입니다. 실험 설계에서는 학생들을 두 교수 중 한 명에게 무작위로 배정하고 학생들의 최종 성적을 비교합니다. 그러나 현실에서는 연구자가 학생들에게 무작위로 한 교수의 수업을 듣도록 강요할 수 없기 때문에 기존의 수업을 그대로 사용하여 연구해야 합니다(준실험 설계). 다시 말하지만, 핵심적인 차이점은 독립 변수의 조건에 대한 무작위 할당입니다. 준실험 설계(학생이 원하는 교수를 선택하는 방식)는 무작위처럼 보일 수 있지만, 실제로는 그렇지 않을 가능성이 높습니다. 예를 들어, 학생들이 스미스 박사의 기대치가 낮다고 들었기 때문에 게으른 학생들은 이 수업을 선호하고, 칸 박사의 기대치가 높기 때문에 똑똑한 학생들은 칸 박사의 수업을 선호할 수 있습니다. 이제 교수의 능력에 관계없이 학생의 최종 성적에 거의 확실하게 영향을 미치는 혼돈 변수(학생의 지능)가 도입됩니다. 따라서 준실험 설계는 실험 설계와 유사하지만(즉, 독립 변수와 종속 변수가 모두 있음) 무작위 할당이 없기 때문에 실험 설계에서와 같은 결론을 합리적으로 도출할 수 없습니다.

종단 간 연구

Another powerful research design is the longitudinal study. Longitudinal studies track the same people over time. Some longitudinal studies last a few weeks, some a few months, some a year or more. Some studies that have contributed a lot to psychology followed the same people over decades. For example, one study followed more than 20,000 Germans for two decades. From these longitudinal data, psychologist Rich Lucas (2003) was able to determine that people who end up getting married indeed start off a bit happier than their peers who never marry. Longitudinal studies like this provide valuable evidence for testing many theories in psychology, but they can be quite costly to conduct, especially if they follow many people for many years.

또 다른 강력한 연구 설계는 종단 연구입니다. 종단 연구는 동일한 사람들을 장기간에 걸쳐 추적합니다. 일부 종단 연구는 몇 주, 몇 달, 1년 이상 지속되기도 합니다. 심리학에 많은 기여를 한 일부 연구는 수십 년에 걸쳐 동일한 사람들을 추적했습니다. 예를 들어, 한 연구에서는 20,000명 이상의 독일인을 20년 동안 추적 관찰했습니다. 심리학자 리치 루카스(2003)는 이러한 종단 데이터를 통해 결혼을 하는 사람들이 결혼을 하지 않는 동료들보다 실제로 조금 더 행복하게 시작한다는 사실을 밝혀낼 수 있었습니다. 이와 같은 종단 연구는 심리학의 많은 이론을 테스트하는 데 유용한 증거를 제공하지만, 특히 많은 사람들을 수년 동안 추적하는 경우 수행 비용이 상당히 많이 들 수 있습니다.

설문

A survey is a way of gathering information, using old-fashioned questionnaires or the Internet. Compared to a study conducted in a psychology laboratory, surveys can reach a larger number of participants at a much lower cost. Although surveys are typically used for correlational research, this is not always the case. An experiment can be carried out using surveys as well. For example, King and Napa (1998) presented participants with different types of stimuli on paper: either a survey completed by a happy person or a survey completed by an unhappy person. They wanted to see whether happy people were judged as more likely to get into heaven compared to unhappy people. Can you figure out the independent and dependent variables in this study? Can you guess what the results were? Happy people (vs. unhappy people; the independent variable) were judged as more likely to go to heaven (the dependent variable) compared to unhappy people!

설문조사는 그냥 설문지나 인터넷을 사용하여 정보를 수집하는 방법입니다. 심리학 실험실에서 실시하는 연구에 비해 설문조사는 훨씬 적은 비용으로 더 많은 수의 참가자에게 도달할 수 있습니다. 설문조사는 일반적으로 상관관계 연구에 사용되지만, 항상 그런 것은 아닙니다. 설문조사를 사용하여 실험을 수행할 수도 있습니다. 예를 들어, King과 Napa(1998) 실험 참가자에게 행복한 사람의 설문조사와 행복하지 않은 사람의 설문조사를 보여주었습니다. 연구진은 행복한 사람이 불행한 사람에 비해 천국에 갈 가능성을 더 높게 평가받는지 알아보고자 했습니다. 이 연구에서 독립 변수와 종속 변수를 알아낼 수 있나요? 결과가 무엇인지 짐작할 수 있나요? 행복한 사람(독립 변수)은 불행한 사람에 비해 천국(종속 변수)에 갈 가능성이 더 높다고 평가받았습니다!

Likewise, correlational research can be conducted without the use of surveys. For instance, psychologists LeeAnn Harker and Dacher Keltner (2001) examined the smile intensity of women’s college yearbook photos. Smiling in the photos was correlated with being married 10 years later!

마찬가지로 설문조사를 사용하지 않고도 상관관계 연구를 수행할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 심리학자 리앤 하커와 다처 켈트너(2001)는 여성 대학 졸업 앨범 사진의 미소 강도를 조사했습니다. 사진 속 미소는 10년 후 결혼과 상관관계가 있었습니다!

연구에서의 균형(trade-off)

Even though there are serious limitations to correlational and quasi-experimental research, they are not poor cousins to experiments and longitudinal designs. In addition to selecting a method that is appropriate to the question, many practical concerns may influence the decision to use one method over another. One of these factors is simply resource availability—how much time and money do you have to invest in the research? (Tip: If you’re doing a senior honor’s thesis, do not embark on a lengthy longitudinal study unless you are prepared to delay graduation!) Often, we survey people even though it would be more precise—but much more difficult—to track them longitudinally. Especially in the case of exploratory research, it may make sense to opt for a cheaper and faster method first. Then, if results from the initial study are promising, the researcher can follow up with a more intensive method.

상관관계 연구와 준실험적 연구에는 심각한 한계가 있지만, 실험 및 종단적 설계보다 못하기만 한 존재는 아닙니다. 질문에 적합한 방법을 선택하는 것 외에도 여러 가지 현실적인 문제가 다른 방법보다 그 방법을 사용하기로 결정하는 데 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다. 이러한 요소 중 하나는 리소스 가용성, 즉 연구에 얼마나 많은 시간과 비용을 투자해야 하는가입니다. (팁: 박사 졸업 논문을 작성하는 경우, 졸업을 연기할 준비가 되어 있지 않다면 긴 종단 연구에 착수하지 마세요!). 사람들을 종단적으로 추적하는 것이 더 정확하지만 훨씬 더 어려워 설문조사를 하는 경우가 많습니다. 특히 탐색적 연구의 경우, 더 저렴하고 빠른 방법을 먼저 선택하는 것이 합리적일 수 있습니다. 그런 다음 초기 연구 결과가 유망하다면 연구자는 더 집중적인 방법으로 후속 연구를 진행할 수 있습니다.

Beyond these practical concerns, another consideration in selecting a research design is the ethics of the study. For example, in cases of brain injury or other neurological abnormalities, it would be unethical for researchers to inflict these impairments on healthy participants. Nonetheless, studying people with these injuries can provide great insight into human psychology (e.g., if we learn that damage to a particular region of the brain interferes with emotions, we may be able to develop treatments for emotional irregularities). In addition to brain injuries, there are numerous other areas of research that could be useful in understanding the human mind but which pose challenges to a true experimental design—such as the experiences of war, long-term isolation, abusive parenting, or prolonged drug use. However, none of these are conditions we could ethically experimentally manipulate and randomly assign people to. Therefore, ethical considerations are another crucial factor in determining an appropriate research design.

이러한 실용적인 문제 외에도 연구 설계를 선택할 때 고려해야 할 또 다른 사항은 연구의 윤리성입니다. 예를 들어, 뇌 손상이나 기타 신경학적 이상이 있는 경우, 연구자가 건강한 참가자에게 이러한 장애를 안기는 것은 비윤리적일 수 있습니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 이러한 부상을 입은 사람들을 연구하면 인간 심리에 대한 훌륭한 통찰력을 얻을 수 있습니다(예: 뇌의 특정 부위 손상이 감정과 상호 작용한다는 사실을 알게 되면 감정 불균형에 대한 치료법을 개발할 수 있을 것입니다). 뇌 손상 외에도 인간의 마음을 이해하는 데 유용할 수 있지만 실제 실험 설계에 어려움을 겪는 연구 분야는 전쟁, 장기 고립, 학대적 양육, 장기간의 약물 사용과 같은 수많은 분야가 있습니다. 그러나 이러한 조건 중 어느 것도 윤리적으로 사람들을 무작위로 할당하도록 조작할 수 없습니다. 따라서 윤리적 고려사항은 적절한 연구 설계를 결정하는 또 다른 중요한 요소입니다.

Translated with DeepL

연구 방법: 왜 필요한가

Just look at any major news outlet and you’ll find research routinely being reported. Sometimes the journalist understands the research methodology, sometimes not (e.g., correlational evidence is often incorrectly represented as causal evidence). Often, the media are quick to draw a conclusion for you. After reading this module, you should recognize that the strength of a scientific finding lies in the strength of its methodology. Therefore, in order to be a savvy consumer of research, you need to understand the pros and cons of different methods and the distinctions among them. Plus, understanding how psychologists systematically go about answering research questions will help you to solve problems in other domains, both personal and professional, not just in psychology.

주요 뉴스 매체를 보면 일상적으로 보도되는 연구 결과를 쉽게 찾아볼 수 있습니다. 기자가 연구 방법론을 이해하는 경우도 있지만 그렇지 않은 경우도 있습니다(예: 상관관계 증거를 인과관계 증거로 잘못 표현하는 경우가 많음). 언론은 종종 성급하게 결론을 내리는 경우가 많습니다. 이 모듈을 읽고 나면 과학적 발견의 힘은 그 방법론의 힘에 있다는 것을 인식해야 합니다. 따라서 연구에 정통한 소비자가 되려면 다양한 방법의 장단점과 이들 간의 차이점을 이해해야 합니다. 또한 심리학자들이 연구 질문에 체계적으로 답하는 방법을 이해하면 심리학뿐만 아니라 개인적, 전문적 영역의 다른 문제를 해결하는 데 도움이 됩니다.

외부 리소스

- Article: Harker and Keltner study of yearbook photographs and marriage

- http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/psp/80/1/112/

- Article: Rich Lucas’s longitudinal study on the effects of marriage on happiness

- http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/psp/84/3/527/

- Article: Spending money on others promotes happiness. Elizabeth Dunn’s research

- https://www.sciencemag.org/content/319/5870/1687.abstract

- Article: What makes a life good?

- http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/psp/75/1/156/

토론 질문

- What are some key differences between experimental and correlational research? 실험 연구와 상관 연구의 주요 차이점은 무엇인가요?

- Why might researchers sometimes use methods other than experiments? 연구자들이 때때로 실험이 아닌 다른 방법을 사용하는 이유는 무엇인가요?

- How do surveys relate to correlational and experimental designs? 설문조사는 상관관계 및 실험 설계와 어떤 관련이 있나요?

Vocabulary

- Confounds

- Factors that undermine the ability to draw causal inferences from an experiment.

- Correlation

- Measures the association between two variables, or how they go together.

- Dependent variable

- The variable the researcher measures but does not manipulate in an experiment.

- Experimenter expectations

- When the experimenter’s expectations influence the outcome of a study.

- Independent variable

- The variable the researcher manipulates and controls in an experiment.

- Longitudinal study

- A study that follows the same group of individuals over time.

- Operational definitions

- How researchers specifically measure a concept.

- Participant demand

- When participants behave in a way that they think the experimenter wants them to behave.

- Placebo effect

- When receiving special treatment or something new affects human behavior.

- Quasi-experimental design

- An experiment that does not require random assignment to conditions.

- Random assignment

- Assigning participants to receive different conditions of an experiment by chance.

References

- Chiao, J. (2009). Culture–gene coevolution of individualism – collectivism and the serotonin transporter gene. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 277, 529-537. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.1650

- Dunn, E. W., Aknin, L. B., & Norton, M. I. (2008). Spending money on others promotes happiness. Science, 319(5870), 1687–1688. doi:10.1126/science.1150952

- Festinger, L., Riecken, H.W., & Schachter, S. (1956). When prophecy fails. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Harker, L. A., & Keltner, D. (2001). Expressions of positive emotion in women\'s college yearbook pictures and their relationship to personality and life outcomes across adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 112–124.

- King, L. A., & Napa, C. K. (1998). What makes a life good? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 156–165.

- Lucas, R. E., Clark, A. E., Georgellis, Y., & Diener, E. (2003). Re-examining adaptation and the setpoint model of happiness: Reactions to changes in marital status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 527–539.

Authors

Christie Napa ScollonChristie Napa Scollon is an associate professor of psychology at Singapore Management University. She earned her Ph.D. in social/personality psychology from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in psychology from Southern Methodist University. Her research focuses on cultural differences in emotions and life satisfaction.

Christie Napa ScollonChristie Napa Scollon is an associate professor of psychology at Singapore Management University. She earned her Ph.D. in social/personality psychology from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in psychology from Southern Methodist University. Her research focuses on cultural differences in emotions and life satisfaction.

Creative Commons License

Research Designs by Christie Napa Scollon is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

Research Designs by Christie Napa Scollon is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.