성격 평가(Personality Assessment)

성격 평가

By David WatsonUniversity of Notre Dame

이 모듈에서는 성격 평가에 대한 기본적인 개요를 제공합니다. 객관적인 성격 테스트(자기 보고 및 정보 제공자 평가 모두에 기반), 투사적 및 암시적 테스트, 행동/수행 측정에 대해 설명합니다. 각 방법의 기본 특징과 각 접근법의 강점, 약점 및 전반적인 타당성을 검토합니다.

학습 목표

- Appreciate the diversity of methods that are used to measure personality characteristics.

- Understand the logic, strengths and weaknesses of each approach.

- Gain a better sense of the overall validity and range of applications of personality tests.

성격 특성을 측정하는 데 사용되는 다양한 방법을 이해합니다.

각 접근법의 논리, 강점 및 약점을 이해합니다.

성격 테스트의 전반적인 타당성과 적용 범위에 대해 더 잘 이해합니다.

소개

성격은 정상적인 개인의 생각, 감정, 행동, 목표, 관심사를 연구하는 심리학의 한 분야입니다. 따라서 성격은 매우 광범위하고 중요한 심리적 특성을 다룹니다. 또한 이론적 모델에 따라 이러한 특성을 측정하기 위한 전략도 매우 다양합니다. 예를 들어, 인본주의 지향 모델은 사람들이 명확하고 잘 정의된 목표를 가지고 있으며 이를 달성하기 위해 적극적으로 노력한다고 주장합니다(McGregor, McAdams, & Little, 2006). 따라서 자신과 목표에 대해 직접 물어보는 것이 합리적입니다. 이와는 대조적으로, 심리역동 이론에서는 사람들이 자신의 감정과 동기에 대한 통찰력이 부족하기 때문에 자신의 행동이 인식 밖에서 작동하는 프로세스의 영향을 받는다고 제안합니다(예: McClelland, Koestner, & Weinberger, 1989; Meyer & Kurtz, 2006). 사람들이 이러한 프로세스에 대해 잘 모른다는 점을 고려할 때 직접적으로 물어보는 것은 의미가 없습니다. 따라서 이러한 무의식적 요인을 파악하기 위해서는 완전히 다른 접근 방식을 채택해야 합니다. 당연히 연구자들은 중요한 성격 특성을 측정하기 위해 다양한 접근 방식을 채택해 왔습니다. 가장 널리 사용되는 전략은 다음 섹션에 요약되어 있습니다.

객관적인 테스트

정의

객관적 검사(Loevinger, 1957; Meyer & Kurtz, 2006)는 성격을 평가하는 데 가장 친숙하고 널리 사용되는 접근 방식입니다. 객관식 테스트는 제한된 응답 옵션(예: 참 또는 거짓, 매우 동의하지 않음, 약간 동의하지 않음, 약간 동의함, 매우 동의함)을 사용하여 각 항목에 응답하는 표준 항목 집합을 관리합니다. 그런 다음 이러한 항목에 대한 응답은 표준화되고 미리 정해진 방식으로 채점됩니다. 예를 들어, 수다스러움, 자기 주장, 사교성, 모험심, 에너지를 평가하는 항목에 대한 자가 평가 점수를 합산하여 외향적 성격 특성에 대한 전체 점수를 만들 수 있습니다.

"객관적"이라는 용어는 응답 자체보다는 응답자의 응답에 점수를 매기는 데 사용되는 방법을 의미한다는 점을 강조해야 합니다. 마이어와 커츠(2006, 233쪽)는 "이러한 절차가 객관적인 이유는 검사를 시행하는 심리학자가 응시자의 반응을 분류하거나 해석하기 위해 판단에 의존할 필요가 없으며, 의도된 반응이 명확하게 표시되고 기존의 키에 따라 채점된다는 점입니다."라고 언급했습니다. 실제로 사람의 테스트 반응은 매우 주관적일 수 있으며 여러 가지 평가 편향의 영향을 받을 수 있습니다.

객관식 시험의 기본 유형

자체 보고 조치

객관적인 성격 테스트는 두 가지 기본 유형으로 더 세분화할 수 있습니다. 첫 번째 유형은 현대 성격 연구에서 가장 널리 사용되는 유형으로, 사람들에게 자신을 설명하도록 요청합니다. 이 접근 방식은 두 가지 주요 이점을 제공합니다. 첫째, 자기 평가자는 비교할 수 없을 정도로 풍부한 정보에 액세스할 수 있습니다: 자기 자신보다 자신에 대해 더 많이 아는 사람이 어디 있을까요? 특히 자기 평가자는 다른 사람이 쉽게 알 수 없는 자신의 생각, 감정, 동기에 직접 접근할 수 있습니다(Oh, Wang, & Mount, 2011; Watson, Hubbard, & Weise, 2000). 둘째, 사람들에게 자신을 설명하도록 요청하는 것은 성격을 평가하는 가장 간단하고, 쉽고, 비용 효율적인 접근 방식입니다. 예를 들어, 대학생들에게 비교적 간단한 인센티브(예: 추가 학점)를 제공하면서 자기보고 측정을 실시하는 수많은 연구가 진행되었습니다.

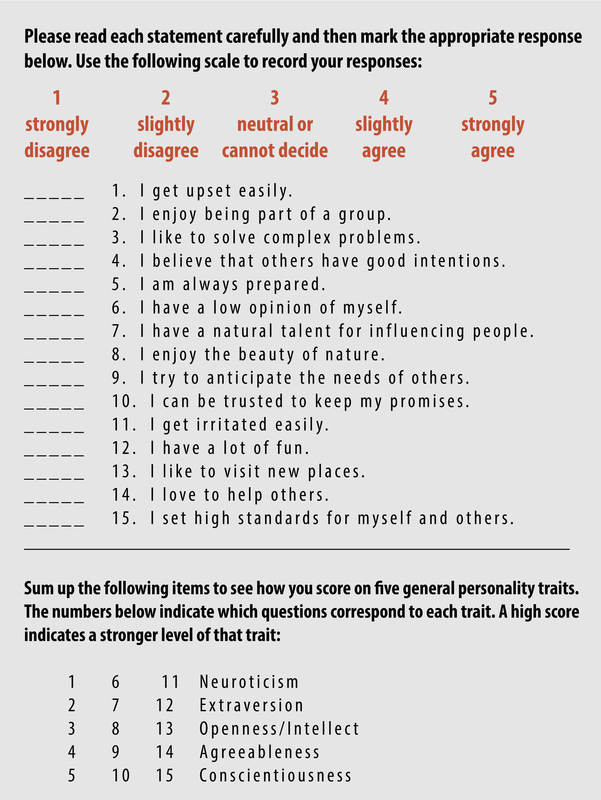

자기보고 측정에 포함된 항목은 단일 단어(예: 단호함), 짧은 문구(예: 에너지가 넘침) 또는 완전한 문장(예: 나는 다른 사람들과 시간을 보내는 것을 좋아함)으로 구성될 수 있습니다. 표 1은 영향력 있는 성격 5요인 모델(FFM)을 구성하는 일반적인 특성인 신경증, 외향성, 개방성, 동의성, 성실성을 평가하는 샘플 자가 보고 척도를 제시합니다(John & Srivastava, 1999; McCrae, Costa, & Martin, 2005). 표 1에 표시된 문장은 퍼블릭 도메인에 있는 성격 관련 콘텐츠의 풍부한 소스인 국제 성격 항목 풀(IPIP)(Goldberg et al., 2006)에 포함된 항목의 수정 버전입니다(IPIP에 대한 자세한 내용은 http://ipip.ori.org/ 참조).

자가 보고 인성 검사는 다양한 중요한 결과와 관련하여 인상적인 타당성을 보여줍니다. 예를 들어, 성실성에 대한 자가 평가는 전반적인 학업 성과(예: 누적 학점 평균; Poropat, 2009)와 직무 성과(Oh, Wang, and Mount, 2011) 모두에 대한 유의미한 예측 변인입니다. Roberts, Kuncel, Shiner, Caspi, Goldberg(2007)는 자기 평가 성격이 직업적 성취도, 이혼, 사망률을 예측한다고 보고했습니다. 마찬가지로 Friedman, Kern, Reynolds(2010)는 생애 초기에 수집한 성격 평가가 수십 년 후 평가한 행복/웰빙, 신체 건강 및 사망 위험과 관련이 있음을 보여주었습니다. 마지막으로, 스스로 보고한 성격은 정신병리와 중요하고 널리 퍼져 있는 연관성이 있습니다. 특히 신경증에 대한 자기 평가는 불안 장애, 우울 장애, 약물 사용 장애, 신체형 장애, 섭식 장애, 성격 및 행동 장애, 조현병/분열형 등 다양한 임상 증후군과 관련이 있습니다(Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt, & Watson, 2010; Mineka, Watson, & Clark, 1998).

그러나 동시에 이 방법은 여러 가지 면에서 한계가 있음이 분명합니다. 첫째, 평가자는 자신을 지나치게 호의적이고 사회적으로 바람직한 방식으로 표현하려는 동기를 가질 수 있습니다(Paunonen & LeBel, 2012). 이는 '고위험 시험', 즉 시험 점수가 개인에 대한 중요한 결정을 내리는 데 사용되는 상황(예: 입사 지원 시)에서 특히 우려되는 부분입니다. 둘째, 성격 평가는 자기 강화 편향(Vazire & Carlson, 2011)을 반영합니다. 즉, 사람들은 자신의 덜 바람직한 특성을 무시(또는 최소한 경시)하고 대신 더 긍정적인 특성에 집중하려는 동기를 갖게 됩니다. 셋째, 자기 평가는 참조 집단 효과의 영향을 받습니다(Heine, Buchtel, & Norenzayan, 2008). 즉, 우리는 부분적으로 사회문화적 참조 집단에 속한 다른 사람들과 어떻게 비교하는지에 따라 자기 인식을 하게 됩니다. 예를 들어, 대부분의 친구들보다 더 열심히 일하는 경향이 있다면, 절대적인 의미에서 특별히 성실하지 않더라도 자신을 상대적으로 성실한 사람으로 인식하게 됩니다.

정보 제공자 평가

또 다른 접근 방식은 그 사람을 잘 아는 사람에게 그 사람의 성격 특성을 설명해 달라고 요청하는 것입니다. 아동이나 청소년의 경우, 정보 제공자는 부모나 교사일 가능성이 높습니다. 나이가 많은 참가자를 대상으로 한 연구에서 정보 제공자는 친구, 룸메이트, 데이트 파트너, 배우자, 자녀 또는 상사일 수 있습니다(Oh et al., 2011; Vazire & Carlson, 2011; Watson et al., 2000).

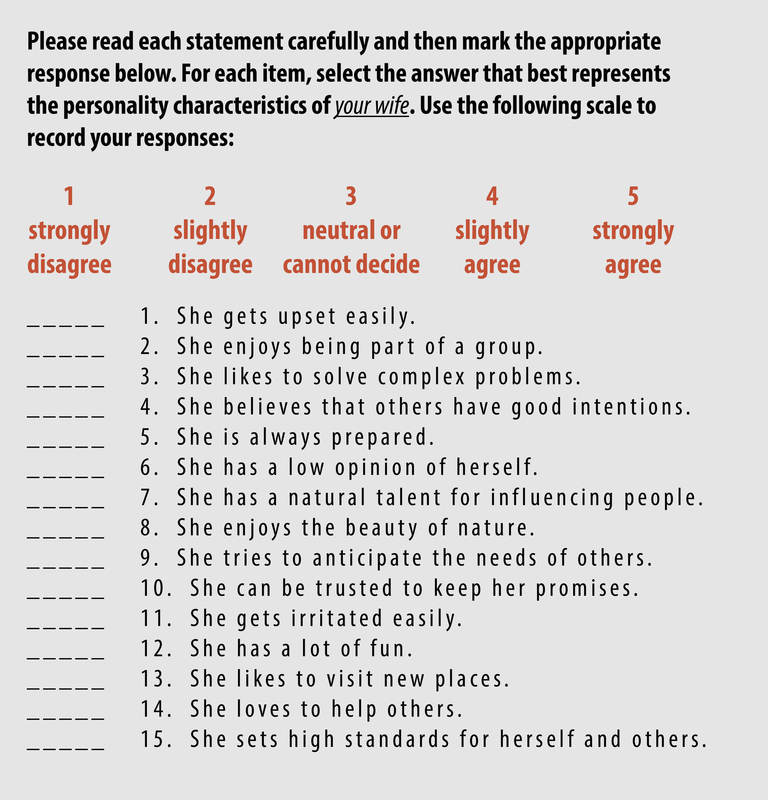

일반적으로 정보 제공자 평가는 자기 평가와 형식이 유사합니다. 자가 평가와 마찬가지로 항목은 단일 단어, 짧은 문구 또는 완전한 문장으로 구성될 수 있습니다. 실제로 많은 인기 있는 도구에는 자가 평가와 정보 제공자 평가 버전이 병행되어 있으며, 자가 평가 측정값을 정보 제공자 평가에 사용할 수 있도록 변환하는 것이 비교적 쉬운 경우가 많습니다. 표 2는 표 1에 표시된 자가 보고 도구를 배우자 평가(이 경우 남편이 아내의 성격 특성을 설명하도록 함)를 얻기 위해 변환하는 방법을 보여줍니다.

정보 제공자 평가는 자기 평가를 수집할 수 없는 경우(예: 어린 아동이나 인지 장애가 있는 성인을 대상으로 연구할 때) 또는 그 타당성이 의심스러운 경우(예: 앞서 언급한 바와 같이 사람들이 고위험 시험 상황에서 완전히 정직하지 않을 수 있는 경우)에 특히 유용합니다. 또한 동일한 특성에 대한 자기 평가와 결합하여 이러한 속성에 대한 보다 신뢰할 수 있고 유효한 측정치를 생성할 수도 있습니다(McCrae, 1994).

정보 제공자 평가는 성격을 평가하는 다른 접근 방식과 비교할 때 몇 가지 장점이 있습니다. 잘 알고 있는 정보 제공자는 자신이 평가하는 사람의 행동 샘플을 많이 관찰할 기회가 있었을 것입니다. 또한, 이러한 판단은 잠재적으로 자기 평가를 왜곡할 수 있는 방어성의 영향을 받지 않을 것으로 추정됩니다(Vazire & Carlson, 2011). 실제로 정보 제공자는 일반적으로 자신의 판단을 정확하게 하려는 강한 인센티브를 가지고 있습니다. Funder와 Dobroth(1987, 409쪽)는 "사회 환경의 사람들에 대한 평가는 누구와 친구가 될지, 피할지, 신뢰하고 불신할지, 고용하고 해고할지 등을 결정하는 데 있어 핵심적인 역할을 합니다."라고 말합니다.

정보 제공자의 성격 평가는 중요한 삶의 결과와 관련하여 앞서 설명한 자기 평가와 비슷한 수준의 타당성을 입증했습니다. 실제로 특정 상황, 특히 평가된 특성이 본질적으로 높은 평가를 받는 경우(예: 지능, 매력, 창의성; Vazire & Carlson, 2011 참조)에는 자기 평가보다 더 나은 성과를 보입니다. 예를 들어, Oh 등(2011)은 정보 제공자 평가가 자기 평가보다 직무 성과와 더 밀접한 관련이 있다는 사실을 발견했습니다. 마찬가지로 올트만스와 터크하이머(2009)는 공군 생도들에 대한 정보원 평가가 자기 평가보다 비자발적 조기 제대를 더 잘 예측한다는 증거를 요약했습니다.

그럼에도 불구하고 정보원 평가에는 특정 문제와 한계가 있습니다. 한 가지 일반적인 문제는 평가자가 이용할 수 있는 관련 정보의 수준입니다(Funder, 2012). 예를 들어, 아무리 좋은 상황에서도 정보 제공자는 자신이 평가하는 사람의 생각, 감정 및 동기에 대한 완전한 접근 권한이 부족합니다. 이 문제는 정보 제공자가 그 사람을 특별히 잘 알지 못하거나 제한된 범위의 상황에서만 그 사람을 볼 때 더욱 커집니다(Funder, 2012; Beer & Watson, 2010).

정보 제공자 평가도 앞서 자가 평가에서 언급한 것과 동일한 응답 편향의 영향을 받습니다. 예를 들어, 이들은 참조 그룹 효과의 영향을 받지 않습니다. 실제로 부모의 평가는 종종 형제자매 대조 효과의 영향을 받아 부모가 자녀 간의 실제 차이의 크기를 과장하는 경우가 많다는 것이 잘 알려져 있습니다(Pinto, Rijsdijk, Frazier-Wood, Asherson, & Kuntsi, 2012). 또한, 많은 연구에서 개인이 자신을 평가할 정보 제공자를 지명(또는 모집)할 수 있습니다. 이 때문에 앞서 언급했듯이 정보 제공자(친구, 친척 또는 연인일 수 있음)가 평가 대상자를 좋아하는 경우가 대부분입니다. 이는 제보자가 지나치게 호의적인 성격 평가를 내릴 수 있다는 것을 의미합니다. 실제로 정보 제공자의 평가는 해당 자체 평가보다 더 호의적일 수 있습니다(Watson & Humrichouse, 2006). 정보 제공자가 비현실적으로 긍정적인 평가를 내리는 이러한 경향을 추천서 효과(Leising, Erbs, & Fritz, 2010)라고 하며, 신혼부부에게 적용하면 허니문 효과(Watson & Humrichouse, 2006)라고도 합니다.

객관식 시험을 분류하는 다른 방법

포괄성

점수의 출처 외에도 성격 테스트에는 적어도 두 가지 중요한 차원이 있습니다. 첫 번째 차원은 도구가 합리적으로 포괄적인 방식으로 성격을 평가하고자 하는 정도에 관한 것입니다. 한 가지 극단적인 예로, 널리 사용되는 많은 측정 도구는 하나의 핵심 속성을 평가하도록 설계되었습니다. 이러한 유형의 척도에는 토론토 분열증 척도(Bagby, Parker, & Taylor, 1994), 로젠버그 자존감 척도(Rosenberg, 1965), 다차원 경험적 회피 설문지(Gamez, Chmielewski, Kotov, Ruggero, & Watson, 2011) 등이 있습니다. 다른 극단적인 예로, 다수의 옴니버스 인벤토리에는 다수의 특정 척도가 포함되어 있으며 합리적이고 포괄적인 방식으로 성격을 측정하는 것을 목적으로 합니다. 이러한 도구에는 캘리포니아 심리 인벤토리(Gough, 1987), 개정된 HEXACO 인성 인벤토리(HEXACO-PI-R)(Lee & Ashton, 2006), 다차원 인성 설문지(Patrick, Curtin, & Tellegen, 2002), NEO 인성 인벤토리-3(NEO-PI-3)(McCrae et al, 2005), 성격 연구 양식(Jackson, 1984), 16가지 성격 요인 설문지(Cattell, Eber, & Tatsuoka, 1980) 등이 있습니다.

대상 특성의 범위

둘째, 성격 특성은 다양한 수준의 폭이나 일반성으로 분류할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 많은 모델은 신경증이나 외향성과 같은 광범위하고 "큰" 특성을 강조합니다. 이러한 일반적인 차원은 몇 가지 뚜렷하면서도 경험적으로 상관관계가 있는 구성 요소 특성으로 나눌 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 외향성의 넓은 차원에는 지배성(외향적인 사람은 자기주장이 강하고 설득력이 있으며 과시적임), 사교성(외향적인 사람은 다른 사람을 찾고 사귀기를 좋아함), 긍정적 정서성(외향적인 사람은 활동적이고 활기차고 쾌활하며 열정적임), 모험성(외향적인 사람은 강렬하고 흥미로운 경험을 즐김) 등의 특정 구성 특성이 포함됩니다.

일부 인기 있는 성격 도구는 광범위하고 일반적인 특성만 평가하도록 설계되었습니다. 예를 들어, 표 1에 표시된 샘플 도구와 유사한 빅 파이브 인벤토리(John & Srivastava, 1999)에는 신경증, 외향성, 개방성, 동의성, 성실성 등의 광범위한 특성을 평가하는 간단한 척도가 포함되어 있습니다. 반면, 앞서 언급한 여러 옴니버스 인벤토리를 포함한 많은 도구는 주로 보다 구체적인 특성을 평가하기 위해 고안되었습니다. 마지막으로, HEXACO-PI-R 및 NEO-PI-3을 포함한 일부 인벤토리는 일반적 특성과 특정 특성 모두를 포괄하도록 명시적으로 설계되었습니다. 예를 들어, NEO-PI-3에는 사교성, 자기주장, 긍정적 감정, 흥분 추구 등 6개의 특정 측면 척도(예: 사교성, 자기주장, 긍정적 감정, 흥분 추구)가 포함되어 있으며, 이를 결합하여 광범위한 외향성 특성을 평가할 수 있습니다.

투영 및 암시적 테스트

투영 테스트

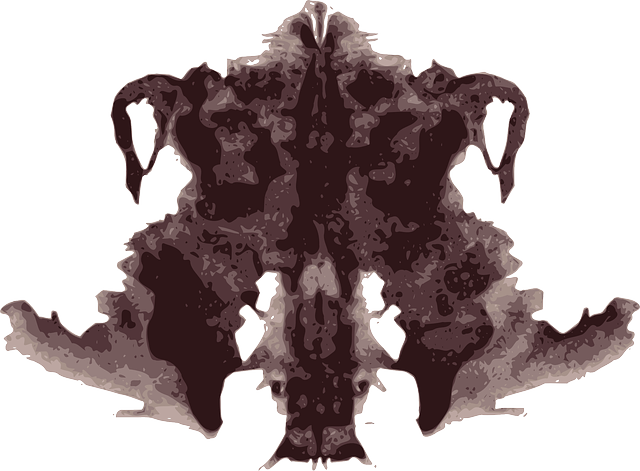

앞서 언급했듯이, 성격 평가에 대한 일부 접근 방식은 중요한 생각, 감정, 동기가 의식적인 인식 밖에서 작용한다는 믿음에 기초합니다. 투사 검사는 이러한 접근 방식의 영향력 있는 초기 사례입니다. 투사 검사는 원래 투사 가설(Frank, 1939; Lilienfeld, Wood, & Garb, 2000)에 기초한 것입니다: 모호한 자극, 즉 여러 가지 방식으로 이해될 수 있는 자극을 묘사하거나 해석하도록 요청받으면 무의식적 욕구, 감정, 경험에 의해 반응이 영향을 받는다는 것입니다(단, 이러한 측정의 기초가 되는 이론적 근거는 시간이 지남에 따라 발전해 왔습니다)(예: Spangler, 1992 참조). 투사 검사의 대표적인 두 가지 예로는 Rorschach 잉크 얼룩 검사(Rorschach, 1921)와 주제 지각 검사(TAT)(Morgan & Murray, 1935)가 있습니다. 전자는 응답자에게 대칭적인 잉크 얼룩을 해석하도록 요청하는 반면, 후자는 일련의 그림에 대한 이야기를 생성하도록 요청합니다.

예를 들어, 한 TAT 그림은 젊은 남자에게 등을 돌린 노인 여성을 묘사하고 있으며, 후자는 다소 당황한 표정으로 아래를 내려다보고 있습니다. 또 다른 사진에는 한 남성이 의문의 세 손을 뒤에서 움켜쥐고 있습니다. 이 사진들을 보고 어떤 이야기를 만들어낼 수 있을까요?

객관식 테스트에 비해 투사식 테스트는 다소 번거롭고 시행에 노동력이 많이 드는 경향이 있습니다. 그러나 가장 큰 과제는 각 응답자가 생성한 광범위한 응답을 점수화할 수 있는 신뢰할 수 있고 유효한 체계를 개발하는 것이었습니다. 가장 널리 사용되는 로샤흐 채점 방식은 Exner(2003)가 개발한 종합 시스템입니다. 가장 영향력 있는 TAT 채점 체계는 1947년에서 1953년 사이에 McClelland, Atkinson 및 동료들에 의해 개발되었으며(McClelland et al., 1989; Winter, 1998 참조), 성취의 필요성과 같은 동기를 평가하는 데 사용할 수 있습니다.

로르샤흐의 타당성은 상당한 논란의 대상이 되어 왔습니다(Lilienfeld 외., 2000; 미후라, 마이어, 두미트라스쿠, 봄벨, 2012; 인성 평가학회, 2005). 대부분의 리뷰는 로샤흐 점수가 중요한 결과를 예측할 수 있는 능력을 어느 정도 보여준다는 점을 인정합니다. 그러나 비판론자들은 표준 자기보고 측정에서 얻은 정보처럼 더 쉽게 얻을 수 있는 다른 정보 이상의 중요한 점진적 정보를 제공하지 못한다고 주장합니다(릴리엔펠드 외., 2000).

타당도 증거는 TAT에 대해 더 인상적입니다. 특히, 성취 욕구에 대한 TAT 기반 측정은 (a) 중요한 기준을 예측하는 데 상당한 타당도를 보이며, (b) 이러한 동기에 대한 객관적인 측정에서 얻은 것 이상의 중요한 정보를 제공한다는 결론을 내렸습니다(McClelland et al., 1989; Spangler, 1992). 또한, 동기의 객관적 측정과 예측적 측정 간의 연관성이 상대적으로 약하다는 점을 고려할 때, McClelland 등(1989)은 후자가 암묵적 동기를 평가하는 등 다소 다른 과정을 활용한다고 주장합니다(Schultheiss, 2008).

암시적 테스트

최근 몇 년 동안 연구자들은 성격에 대한 암묵적 측정법을 사용하기 시작했습니다(Back, Schmuckle, & Egloff, 2009; Vazire & Carlson, 2011). 이러한 테스트는 사람들이 이전 경험과 행동을 바탕으로 특정 개념 사이에 자동적 또는 암묵적 연관성을 형성한다는 가정을 기반으로 합니다. 두 개념(예: 나와 독단적)이 서로 강하게 연관되어 있다면, 연관성이 덜한 두 개념(예: 나와 수줍음)보다 더 빠르고 쉽게 함께 분류되어야 합니다. 이러한 측정에 대한 타당성 증거는 아직 상대적으로 부족하지만, 지금까지의 결과는 고무적입니다: 예를 들어, Back 등(2009)의 연구에 따르면 FFM 성격 특성의 암묵적 측정은 동일한 특성의 객관적 측정 점수를 통제한 후에도 행동을 예측하는 것으로 나타났습니다.

행동 및 성과 측정

마지막 접근 방식은 직접적인 행동 샘플에서 중요한 성격 특성을 추론하는 것입니다. 예를 들어, Funder와 Colvin(1988)은 이성 쌍의 참가자를 실험실에 데려와 5분 동안 '친해지기' 대화를 나누게 한 다음, 평가자들이 이러한 상호작용의 비디오 테이프를 시청한 후 다양한 성격 특성에 대해 점수를 매겼습니다. Mehl, Gosling, Pennebaker(2006)는 전자 활성화 녹음기(EAR)를 사용하여 이틀 동안 참가자의 자연 환경에서 주변 소리 샘플을 수집하고, EAR 기반 점수를 자기 평가 및 관찰자 평가 성격 측정과 연관시켰습니다. 예를 들어, 이틀 동안 말을 더 자주 하는 것은 자기 및 관찰자가 평가한 외향성과 유의미한 관련이 있었습니다. 마지막 예로, 고슬링, 고, 마나렐리, 모리스(2002)는 관찰자를 대학생의 침실로 보낸 다음 빅 5 특성에 대한 학생의 성격 특성을 평가하도록 했습니다. 관찰자의 평균 평가는 다섯 가지 특성 모두에 대한 참가자의 자기 평가와 유의미한 상관관계가 있었습니다. 후속 분석 결과, 성실한 학생은 방을 더 깔끔하게 정리한 반면, 경험에 대한 개방성이 높은 학생은 더 다양한 책과 잡지를 가지고 있었습니다.

행동 측정은 성격을 평가하는 다른 접근 방식에 비해 몇 가지 장점이 있습니다. 첫째, 행동을 직접 샘플링하기 때문에 객관적인 테스트에서 점수를 왜곡할 수 있는 응답 편향(예: 자기 강화 편향, 참조 그룹 효과)의 영향을 받지 않습니다. 둘째, Mehl 외(2006) 및 Gosling 외(2002) 연구에서 알 수 있듯이, 이 접근법은 사람들을 일상 생활과 자연 환경에서 연구할 수 있으므로 다른 방법의 인위성을 피할 수 있습니다(Mehl 외., 2006). 마지막으로, 이 접근법은 사람들이 생각하거나 느끼는 것과는 반대로 실제로 무엇을 하는지를 평가하는 유일한 접근법입니다(Baumeister, Vohs, & Funder, 2007 참조).

그러나 동시에 이 접근법에는 몇 가지 단점도 있습니다. 이 평가 전략은 객관적인 테스트, 특히 자기보고를 사용하는 것보다 훨씬 더 번거롭고 노동 집약적입니다. 또한, 투사적 테스트와 마찬가지로 행동 측정은 풍부한 데이터를 생성하며, 이를 신뢰할 수 있고 유효한 방식으로 채점해야 합니다. 마지막으로, 아무리 야심찬 연구라 할지라도 비교적 적은 수의 행동 샘플만 확보하기 때문에 개인의 실제 특성을 다소 왜곡된 시각으로 볼 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 특정 날에 '친해지기' 대화를 나누는 동안의 행동에는 그 날에만 나타나는 여러 가지 일시적인 영향(예: 스트레스 수준, 전날 밤 수면의 질)이 반영될 수밖에 없습니다.

결론

성격을 평가하는 어떤 방법도 완벽하거나 무오류한 것은 없으며, 각 주요 방법에는 장점과 한계가 모두 있습니다. 연구자들은 다양한 접근법을 사용함으로써 단일 방법의 한계를 극복하고 성격에 대한 보다 완전하고 통합적인 관점을 개발할 수 있습니다.

Discussion Questions

- Under what conditions would you expect self-ratings to be most similar to informant ratings? When would you expect these two sets of ratings to be most different from each other?

- The findings of Gosling, et al. (2002) demonstrate that we can obtain important clues about students’ personalities from their dorm rooms. What other aspects of people’s lives might give us important information about their personalities?

- Suppose that you were planning to conduct a study examining the personality trait of honesty. What method or methods might you use to measure it?

Vocabulary

- Big Five

- Five, broad general traits that are included in many prominent models of personality. The five traits are neuroticism (those high on this trait are prone to feeling sad, worried, anxious, and dissatisfied with themselves), extraversion (high scorers are friendly, assertive, outgoing, cheerful, and energetic), openness to experience (those high on this trait are tolerant, intellectually curious, imaginative, and artistic), agreeableness (high scorers are polite, considerate, cooperative, honest, and trusting), and conscientiousness (those high on this trait are responsible, cautious, organized, disciplined, and achievement-oriented).

- High-stakes testing

- Settings in which test scores are used to make important decisions about individuals. For example, test scores may be used to determine which individuals are admitted into a college or graduate school, or who should be hired for a job. Tests also are used in forensic settings to help determine whether a person is competent to stand trial or fits the legal definition of sanity.

- Honeymoon effect

- The tendency for newly married individuals to rate their spouses in an unrealistically positive manner. This represents a specific manifestation of the letter of recommendation effect when applied to ratings made by current romantic partners. Moreover, it illustrates the very important role played by relationship satisfaction in ratings made by romantic partners: As marital satisfaction declines (i.e., when the “honeymoon is over”), this effect disappears.

- Implicit motives

- These are goals that are important to a person, but that he/she cannot consciously express. Because the individual cannot verbalize these goals directly, they cannot be easily assessed via self-report. However, they can be measured using projective devices such as the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT).

- Letter of recommendation effect

- The general tendency for informants in personality studies to rate others in an unrealistically positive manner. This tendency is due a pervasive bias in personality assessment: In the large majority of published studies, informants are individuals who like the person they are rating (e.g., they often are friends or family members) and, therefore, are motivated to depict them in a socially desirable way. The term reflects a similar tendency for academic letters of recommendation to be overly positive and to present the referent in an unrealistically desirable manner.

- Projective hypothesis

- The theory that when people are confronted with ambiguous stimuli (that is, stimuli that can be interpreted in more than one way), their responses will be influenced by their unconscious thoughts, needs, wishes, and impulses. This, in turn, is based on the Freudian notion of projection, which is the idea that people attribute their own undesirable/unacceptable characteristics to other people or objects.

- Reference group effect

- The tendency of people to base their self-concept on comparisons with others. For example, if your friends tend to be very smart and successful, you may come to see yourself as less intelligent and successful than you actually are. Informants also are prone to these types of effects. For instance, the sibling contrast effect refers to the tendency of parents to exaggerate the true extent of differences between their children.

- Reliablility

- The consistency of test scores across repeated assessments. For example, test-retest reliability examines the extent to which scores change over time.

- Self-enhancement bias

- The tendency for people to see and/or present themselves in an overly favorable way. This tendency can take two basic forms: defensiveness (when individuals actually believe they are better than they really are) and impression management (when people intentionally distort their responses to try to convince others that they are better than they really are). Informants also can show enhancement biases. The general form of this bias has been called the letter-of-recommendation effect, which is the tendency of informants who like the person they are rating (e.g., friends, relatives, romantic partners) to describe them in an overly favorable way. In the case of newlyweds, this tendency has been termed the honeymoon effect.

- Sibling contrast effect

- The tendency of parents to use their perceptions of all of their children as a frame of reference for rating the characteristics of each of them. For example, suppose that a mother has three children; two of these children are very sociable and outgoing, whereas the third is relatively average in sociability. Because of operation of this effect, the mother will rate this third child as less sociable and outgoing than he/she actually is. More generally, this effect causes parents to exaggerate the true extent of differences between their children. This effect represents a specific manifestation of the more general reference group effect when applied to ratings made by parents.

- Validity

- Evidence related to the interpretation and use of test scores. A particularly important type of evidence is criterion validity, which involves the ability of a test to predict theoretically relevant outcomes. For example, a presumed measure of conscientiousness should be related to academic achievement (such as overall grade point average).

References

- Back, M. D., Schmukle, S. C., & Egloff, B. (2009). Predicting actual behavior from the explicit and implicit self-concept of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 533–548.

- Bagby, R. M., Parker, J. D. A., Taylor, G. J. (1994). The Twenty-Item Toronto Alexithymia Scale: I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 38, 23–32.

- Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., & Funder, D. C. (2007). Psychology as the science of self-reports and finger movements: Whatever happened to actual behavior? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2, 396–403.

- Beer, A., & Watson, D. (2010). The effects of information and exposure on self-other agreement. Journal of Research in Personality, 44, 38–45.

- Cattell, R. B., Eber, H. W, & Tatsuoka, M. M. (1980). Handbook for the Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire (16PF). Champaign, IL: Institute for Personality and Ability Testing.

- Exner, J. E. (2003). The Rorschach: A comprehensive system (4th ed.). New York, NY: Wiley.

- Frank, L. K. (1939). Projective methods for the study of personality. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 8, 389–413.

- Friedman, H. S., Kern, K. L., & Reynolds, C. A. (2010). Personality and health, subjective well-being, and longevity. Journal of Personality, 78, 179–215.

- Funder, D. C. (2012). Accurate personality judgment. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21, 177–182.

- Funder, D. C., & Colvin, C. R. (1988). Friends and strangers: Acquaintanceship, agreement, and the accuracy of personality judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55, 149–158.

- Funder, D. C., & Dobroth, K. M. (1987). Differences between traits: Properties associated with interjudge agreement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 409–418.

- Gamez, W., Chmielewski, M., Kotov, R., Ruggero, C., & Watson, D. (2011). Development of a measure of experiential avoidance: The Multidimensional Experiential Avoidance Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 23, 692–713.

- Goldberg, L. R., Johnson, J. A., Eber, H. W., Hogan, R., Ashton, M. C., Cloninger, C. R., & Gough, H. C. (2006). The International Personality Item Pool and the future of public-domain personality measures. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 84–96.

- Gosling, S. D., Ko, S. J., Mannarelli, T., & Morris, M. E. (2002). A room with a cue: Personality judgments based on offices and bedrooms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 379–388.

- Gough, H. G. (1987). California Psychological Inventory [Administrator’s guide]. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Heine, S. J., Buchtel, E. E., & Norenzayan, A. (2008). What do cross-national comparisons of personality traits tell us? The case of conscientiousness. Psychological Science, 19, 309–313.

- Jackson, D. N. (1984). Personality Research Form manual (3rd ed.). Port Huron, MI: Research Psychologists Press.

- John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The big five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 102–138). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Kotov, R., Gamez, W., Schmidt, F., & Watson, D. (2010). Linking “big” personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 768–821.

- Lee, K., & Ashton, M. C. (2006). Further assessment of the HEXACO Personality Inventory: Two new facet scales and an observer report form. Psychological Assessment, 18, 182–191.

- Leising, D., Erbs, J., & Fritz, U. (2010). The letter of recommendation effect in informant ratings of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98, 668–682.

- Lilienfeld, S. O., Wood, J. M., & Garb, H. N. (2000). The scientific status of projective techniques. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 1, 27–66.

- Loevinger, J. (1957). Objective tests as instruments of psychological theory. Psychological Reports, 3, 635–694.

- McClelland, D. C., Koestner, R., & Weinberger, J. (1989). How do self-attributed and implicit motives differ? Psychological Review, 96, 690–702.

- McCrae, R. R. (1994). The counterpoint of personality assessment: Self-reports and observer ratings. Assessment, 1, 159–172.

- McCrae, R. R., Costa, P. T., Jr., & Martin, T. A. (2005). The NEO-PI-3: A more readable Revised NEO Personality Inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 84, 261–270.

- McGregor, I., McAdams, D. P., & Little, B. R. (2006). Personal projects, life stories, and happiness: On being true to traits. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 551–572.

- Mehl, M. R., Gosling, S. D., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2006). Personality in its natural habitat: Manifestations and implicit folk theories of personality in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 862–877.

- Meyer, G. J., & Kurtz, J. E. (2006). Advancing personality assessment terminology: Time to retire “objective” and “projective” as personality test descriptors. Journal of Personality Assessment, 87, 223–225.

- Mihura, J. L., Meyer, G. J., Dumitrascu, N., & Bombel, G. (2012). The validity of individual Rorschach variables: Systematic Reviews and meta-analyses of the Comprehensive System. Psychological Bulletin. (Advance online publication.) doi:10.1037/a0029406

- Mineka, S., Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1998). Comorbidity of anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. Annual Review of Psychology, 49, 377–412.

- Morgan, C. D., & Murray, H. A. (1935). A method for investigating fantasies. The Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry, 34, 389–406.

- Oh, I.-S., Wang, G., & Mount, M. K. (2011). Validity of observer ratings of the five-factor model of personality traits: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 762–773.

- Oltmanns, T. F., & Turkheimer, E. (2009). Person perception and personality pathology. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18, 32–36.

- Patrick, C. J., Curtin, J. J., & Tellegen, A. (2002). Development and validation of a brief form of the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 14, 150–163.

- Paunonen, S. V., & LeBel, E. P. (2012). Socially desirable responding and its elusive effects on the validity of personality assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103, 158–175.

- Pinto, R., Rijsdijk, F., Frazier-Wood, A. C., Asherson, P., & Kuntsi, J. (2012). Bigger families fare better: A novel method to estimate rater contrast effects in parental ratings on ADHD symptoms. Behavior Genetics, 42, 875–885.

- Poropat, A. E. (2009). A meta-analysis of the five-factor model of personality and academic performance. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 322–338.

- Roberts, B. W., Kuncel, N. R., Shiner, R., Caspi, A., & Goldberg, L. R. (2007). The power of personality: The comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2, 313–345.

- Rorschach, H. (1942) (Original work published 1921). Psychodiagnostik [Psychodiagnostics]. Bern, Switzerland: Bircher.

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Schultheiss, O. C. (2008). Implicit motives. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (3rd ed.) (pp. 603–633). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Society for Personality Assessment. (2005). The status of the Rorschach in clinical and forensic practice: An official statement by the Board of Trustees of the Society for Personality Assessment. Journal of Personality Assessment, 85, 219–237.

- Spangler, W. D. (1992). Validity of questionnaire and TAT measures of need for achievement: Two meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 140–154.

- Vazire, S., & Carlson, E. N. (2011). Others sometimes know us better than we know ourselves. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20, 104–108.

- Watson, D., & Humrichouse, J. (2006). Personality development in emerging adulthood: Integrating evidence from self- and spouse-ratings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 959–974.

- Watson, D., Hubbard, B., & Wiese, D. (2000). Self-other agreement in personality and affectivity: The role of acquaintanceship, trait visibility, and assumed similarity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 546–558.

- Winter, D. G. (1998). Toward a science of personality psychology: David McClelland’s development of empirically derived TAT measures. History of Psychology, 1, 130–153.

Authors

David WatsonDavid Watson is the Andrew J. McKenna Professor of Psychology at the University of Notre Dame. He is well known for his work in personality, clinical, and mood assessment. He and his colleagues have created a number of widely used instruments, including the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS).

David WatsonDavid Watson is the Andrew J. McKenna Professor of Psychology at the University of Notre Dame. He is well known for his work in personality, clinical, and mood assessment. He and his colleagues have created a number of widely used instruments, including the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS).

Creative Commons License

Personality Assessment by David Watson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

Personality Assessment by David Watson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.