매력과 아름다움(Attraction and Beauty)

끌림과 아름다움

By Robert G. Franklin and Leslie ZebrowitzAnderson University, Brandeis University

더 매력적인 사람은 더 긍정적인 첫인상을 남깁니다. 이러한 효과를 매력 후광이라고 하며, 매력적인 얼굴, 몸매, 목소리를 가진 사람을 판단할 때 나타납니다. 또한 연애, 우정, 가족 관계, 교육, 직장, 형사 사법 등 광범위한 영역에서 매력적인 사람에게 유리하게 작용하는 등 중요한 사회적 결과를 낳습니다. 매력을 높이는 신체적 특성으로는 젊음, 대칭성, 평균성, 남성의 남성성, 여성의 여성성 등이 있습니다. 긍정적인 표정과 행동도 사람의 매력에 대한 평가를 높입니다. 특정 사람을 매력적으로 느끼는 이유를 설명하기 위해 문화적, 인지적, 진화론적, 과잉 일반화 설명이 제시되었습니다. 진화론적 설명은 후광 효과와 관련된 인상이 정확할 것이라고 예측하는 반면, 다른 설명은 그렇지 않습니다. 연구 증거가 어느 정도 정확성을 보여주기는 하지만, 더 매력적인 사람들에게 나타나는 긍정적인 반응을 만족스럽게 설명하기에는 너무 약합니다.

학습 목표

- Learn the advantages of attractiveness in social situations.

- Know what features are associated with facial, body, and vocal attractiveness.

- Understand the universality and cultural variation in attractiveness.

- Learn about the mechanisms proposed to explain positive responses to attractiveness.

- 사회적 상황에서 매력의 이점에 대해 알아보세요.

얼굴, 신체 및 보컬 매력과 관련된 특징을 파악합니다.

매력의 보편성과 문화적 다양성을 이해합니다.

매력에 대한 긍정적인 반응을 설명하기 위해 제안된 메커니즘에 대해 알아보세요.

우리는 매력에 대해 양면성을 가지고 있습니다. 우리는 "책 표지만 보고 판단하지 말라"는 말을 들었고, "아름다움은 피부 깊숙한 곳에 있다"는 말을 들었습니다. 이러한 경고에서 알 수 있듯이, 우리는 자연스럽게 외모로 사람을 판단하고 아름다운 사람을 선호하는 경향이 있습니다. 사람들의 얼굴은 물론 신체와 목소리의 매력은 연애 파트너를 선택하는 데 영향을 미칠 뿐만 아니라 연애와 무관한 영역에서 사람들의 특성과 중요한 사회적 결과에 대한 인상에도 영향을 미칩니다. 이 모듈에서는 이러한 매력의 영향을 검토하고 어떤 신체적 특성이 매력을 높이는지, 그 이유는 무엇인지 살펴봅니다.

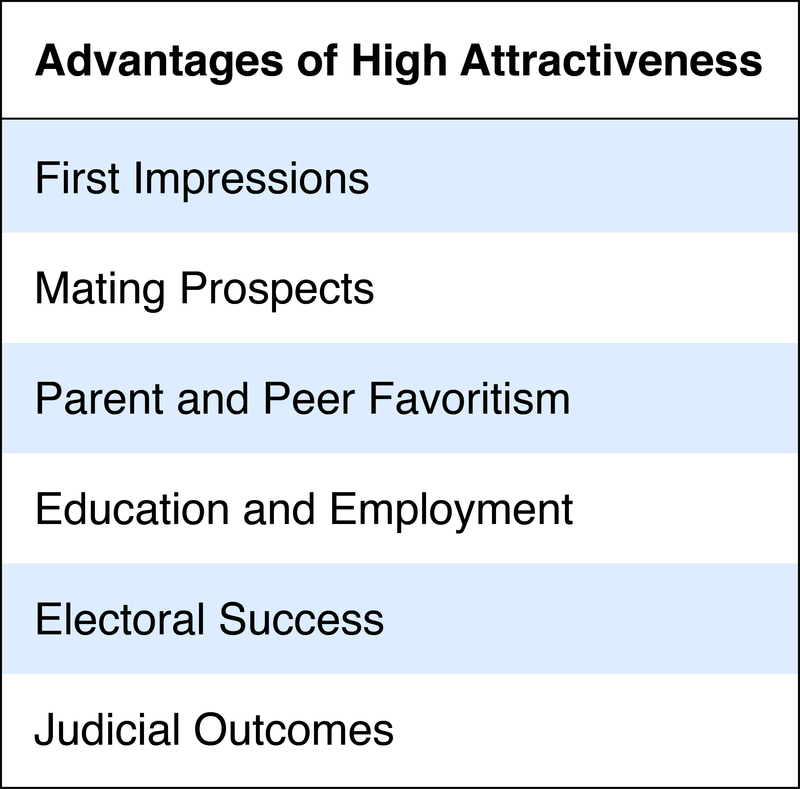

매력의 장점

매력은 자산입니다. 로맨틱한 환경에서 매력이 중요하다는 것은 놀라운 일이 아니지만, 매력은 다른 많은 사회적 영역에서도 그 이점을 발견할 수 있습니다. 더 매력적인 사람들은 더 지적이고, 건강하며, 신뢰할 수 있고, 사교적인 것으로 간주되는 등 다양한 특성에서 더 긍정적으로 인식됩니다. 얼굴의 매력에 대한 연구가 가장 많이 진행되었지만(Eagly, Ashmore, Makhijani, & Longo, 1991), 신체적 또는 보컬적 매력도가 높은 사람들도 더 긍정적인 인상을 남깁니다(Riggio, Widaman, Tucker, & Salinas, 1991; Zuckerman & Driver, 1989). 이러한 이점을 매력 후광 효과라고 하며, 이는 널리 퍼져 있습니다. 매력적인 성인은 매력적이지 않은 또래보다 더 긍정적으로 평가될 뿐만 아니라 매력적인 아기조차도 부모가 더 긍정적으로 바라보고, 낯선 사람은 더 건강하고, 애정이 넘치고, 어머니에게 애착이 있고, 쾌활하고, 반응이 좋고, 호감이 가고, 똑똑하다고 생각합니다(Langlois et al., 2000). 교사는 매력적인 어린이를 더 좋아할 뿐만 아니라 잘못 행동할 가능성이 적고, 더 똑똑하며, 고급 학위를 받을 가능성도 더 높다고 인식합니다. 볼리비아 열대우림의 고립된 원주민 부족에서도 얼굴이 매력적이라고 판단되는 사람들에 대한 긍정적인 인상이 여러 문화권에서 나타납니다(Zebrowitz et al., 2012).

매력은 긍정적인 인상을 줄 뿐만 아니라 다양한 사회적 상황에서도 이점을 제공합니다. 한 고전적인 연구에 따르면, 성격이나 지능을 측정하는 것이 아니라 매력을 측정하여 소개팅에서 무작위로 짝을 이룬 개인이 상대방과 다시 연락하고 싶은지 여부를 예측했습니다(Walster, Aronson, Abrahams, & Rottman, 1966). 매력은 여성보다 남성의 연애 선호도에 더 큰 영향을 미치지만(Feingold, 1990), 남녀 모두에게 상당한 영향을 미칩니다. 매력적인 남성과 여성은 덜 매력적인 동료보다 일찍 성적으로 활동적입니다. 또한 남성의 매력은 장기적인 성 파트너가 아닌 단기적인 성 파트너의 수와 양의 상관관계가 있는 반면, 여성은 그 반대입니다(Rhodes, Simmons, & Peters, 2005). 이러한 결과는 남성의 성공은 단기적인 짝짓기 기회(짝이 많을수록 자손의 확률이 높아짐)에 더 많이 의존하고 여성의 성공은 장기적인 짝짓기 기회(헌신적인 짝이 자손의 생존 확률을 높임)에 더 많이 의존하기 때문에 남녀 모두의 매력이 생식 성공과 관련이 있다는 것을 시사합니다. 물론 모든 사람이 가장 매력적인 짝을 찾을 수 있는 것은 아니며, 연구에 따르면 '매칭' 효과도 있습니다. 매력적일수록 매력적이지 않은 사람보다 매력도가 높은 사람과 데이트하기를 기대하며(Montoya, 2008), 실제 연애 중인 커플의 매력도도 비슷하다고 합니다(Feingold, 1988). 매력적인 사람의 매력은 플라토닉 우정에도 영향을 미칩니다. 매력적인 사람은 또래 친구들에게 더 인기가 많으며, 이는 유아기에도 나타납니다(Langlois et al., 2000).

매력 후광은 그러한 차이를 만들 것이라고 기대하지 않는 상황에서도 발견됩니다. 예를 들어, 낯선 사람이 사진이 첨부된 대학원 지원서가 들어 있는 분실 편지를 우편으로 보내면 매력적이지 않은 사람보다 매력적인 사람에게 도움을 줄 가능성이 더 높다는 연구 결과가 있습니다(Benson, Karabenick, & Lerner, 1976). 다양한 직종의 채용 결정에서 더 매력적인 지원자가 선호되며, 매력적인 사람은 더 높은 급여를 받습니다(Dipboye, Arvey, & Terpstra, 1977; Hamermesh & Biddle, 1994; Hosoda, Stone-Romero, & Coats, 2003). 얼굴의 매력은 정치적, 사법적 결과에도 영향을 미칩니다. 매력적인 국회의원 후보가 당선될 확률이 높고, 범죄로 유죄 판결을 받은 피고인이 더 가벼운 형을 받을 확률이 높습니다(Stewart, 1980; Verhulst, Lodge, & Lavine, 2010). 신체적 매력은 사회적 결과에도 영향을 미칩니다. 비슷한 고등학교 성적에도 불구하고 정상 체중의 대학 지원자보다 과체중 지원자의 입학 비율이 더 적고(Canning & Mayer, 1966), 부모가 과체중 자녀의 교육비를 부담할 가능성이 낮으며(Crandall, 1991), 동일한 자격 요건에도 불구하고 과체중인 경우 취업 추천을 덜 받는다고 합니다(Larkin & Pines, 1979). 목소리 품질은 사회적 결과에도 영향을 미칩니다. 대학생들은 더 매력적인 목소리를 가진 다른 학생들과 어울리고 싶은 욕구가 더 크며(Miyake & Zuckerman, 1993), 더 매력적인 목소리를 가진 정치인이 선거에서 승리할 가능성이 더 높습니다(Gregory & Gallagher, 2002; Tigue, Borak, O'Connor, Schandl, & Feinberg, 2012). 이러한 연구 결과는 표지만 보고 책을 판단해서는 안 된다는 통념이 틀렸음을 명확하게 보여주는 몇 가지 사례에 불과합니다.

무엇이 사람을 매력적으로 만들까요?

무엇이 사람을 매력적으로 만드는지 조사한 대부분의 연구는 성적 매력에 초점을 맞췄습니다. 하지만 매력은 다면적인 현상입니다. 우리는 유아(양육자적 매력), 친구(공동체적 매력), 리더(존경심적 매력)에게 매력을 느낍니다. 어떤 얼굴 특성은 보편적으로 매력적일 수 있지만, 다른 얼굴 특성은 "보는 사람의 눈"뿐만 아니라 판단하는 개인에 따라 달라집니다. 예를 들어, 아기 같은 얼굴 특성은 유아의 얼굴 매력에는 필수적이지만 남성 리더의 카리스마를 떨어뜨리며(Hildebrandt & Fitzgerald, 1979; Sternglanz, Gray, & Murakami, 1977; Mueller & Mazur, 1996), 특정 얼굴 특성의 성적 매력은 보는 사람이 누군가를 단기적인 배우자로 평가하는지 장기적인 배우자로 평가하는지에 따라 다릅니다(Little, Jones, Penton-Voak, Burt, & Perrett, 2002). 매력이 다면적이라는 사실은 매력이 성적 선호도와 미적 선호도가 결합된 이중적 과정이라는 연구에서도 강조됩니다. 보다 구체적으로, 남성의 매력에 대한 여성의 전반적인 평가는 남성이 잠재적인 데이트 상대와 같은 성적인 상황에서 얼마나 매력적인지에 대한 평가와 잠재적인 실험실 파트너와 같은 비성적인 상황에서 얼마나 매력적인지에 대한 평가로 설명됩니다(Franklin & Adams, 2009). 성적 매력과 비성적 매력을 판단하는 데 서로 다른 뇌 영역이 관여한다는 사실이 밝혀지면서 이중적인 과정이 더욱 명확해졌습니다(Franklin & Adams, 2010).

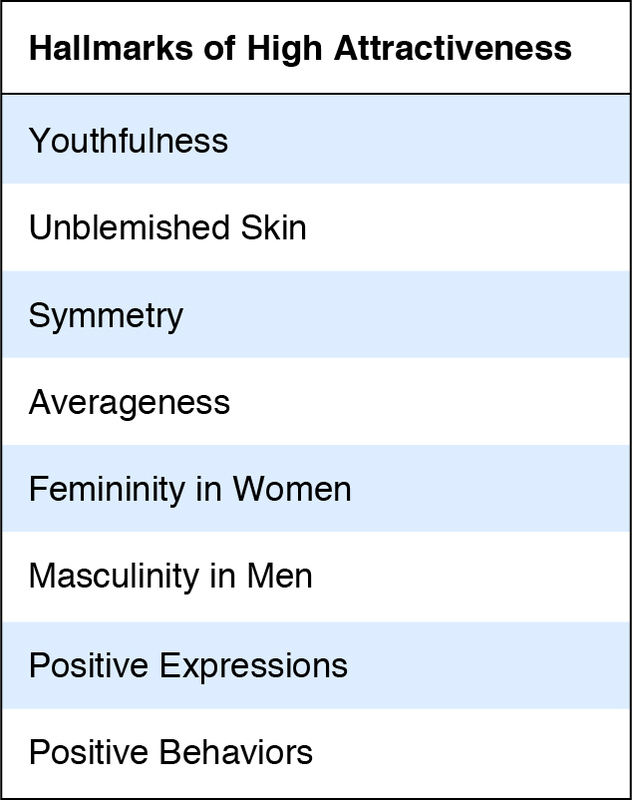

더 매력적인 얼굴 특징에는 젊음, 잡티 없는 피부, 대칭, 인구 평균에 가까운 얼굴 구성, 여성의 여성성 또는 남성성이 포함되며, 작은 턱, 높은 눈썹, 작은 코는 더 여성적이거나 덜 남성적인 특징 중 일부입니다. 마찬가지로 여성은 여성스럽고 고음이 높을수록, 남성은 남성스럽고 저음이 높을수록 더 매력적입니다(Collins, 2000; Puts, Barndt, Welling, Dawood, & Burriss, 2011). 신체의 경우, 매력을 높이는 특징으로는 성별에 따른 허리 대 엉덩이 비율(여성은 엉덩이보다 허리가 좁지만 남성은 그렇지 않은 경우)과 쇠약하거나 심하게 비만하지 않은 체격이 있습니다. 비만에 대한 부정적인 반응은 어릴 때부터 나타납니다. 예를 들어, 한 고전적인 연구에 따르면 어린이들에게 그림에 묘사된 다양한 장애를 가진 어린이에 대한 선호도를 순위로 매기도록 했을 때 과체중 어린이는 손이 없는 어린이, 휠체어에 앉은 어린이, 얼굴에 흉터가 있는 어린이보다 더 낮은 순위를 차지했습니다(Richardson, Goodman, Hastorf, & Dornbusch, 1961).

매력에 영향을 미치는 신체적 특성은 여러 가지가 있지만, 어느 한 가지 특성이 높은 매력의 필요조건이나 충분조건은 아닌 것으로 보입니다. 완벽하게 대칭인 얼굴을 가진 사람이라도 눈이 너무 가깝거나 너무 멀리 떨어져 있으면 매력적이지 않을 수 있습니다. 피부가 아름다운 여성이나 남성적인 얼굴 특징을 가진 남성이 매력적이지 않다고 생각할 수도 있습니다. 완벽하게 평균적인 얼굴을 가진 사람이라도 그 얼굴이 90세 인구의 평균이라면 매력적이지 않을 수 있습니다. 이러한 예는 높은 매력을 위해서는 여러 가지 특징의 조합이 필요하다는 것을 시사합니다. 남성이 여성에게 매력을 느끼는 경우, 바람직한 조합에는 젊음, 성적 성숙함, 접근성이 포함되는 것으로 보입니다(Cunningham, 1986). 반대로, 평균적인 얼굴과 극단적으로 거리가 먼 것과 같은 한 가지 특성만으로는 매력도가 낮습니다. 일반적으로 특정 신체적 특성이 더 매력적으로 여겨지지만, 해부학적 구조는 운명이 아닙니다. 매력은 미소 및 얼굴 표정과 긍정적인 관련이 있으며(Riggio & Friedman, 1986), "예쁜 것은 예쁜 대로"라는 격언에도 어느 정도 진실이 있습니다. 연구에 따르면 학생들은 강사의 행동이 차갑고 거리감이 느껴질 때보다 따뜻하고 친근할 때 강사의 외모가 매력적이라고 판단할 가능성이 높으며(Nisbett & Wilson, 1977), 사람들은 여성의 성격에 대한 호의적인 묘사가 있을 때 여성을 더 신체적으로 매력적이라고 평가합니다(Gross & Crofton, 1977).

특정 사람들은 왜 매력적일까요?

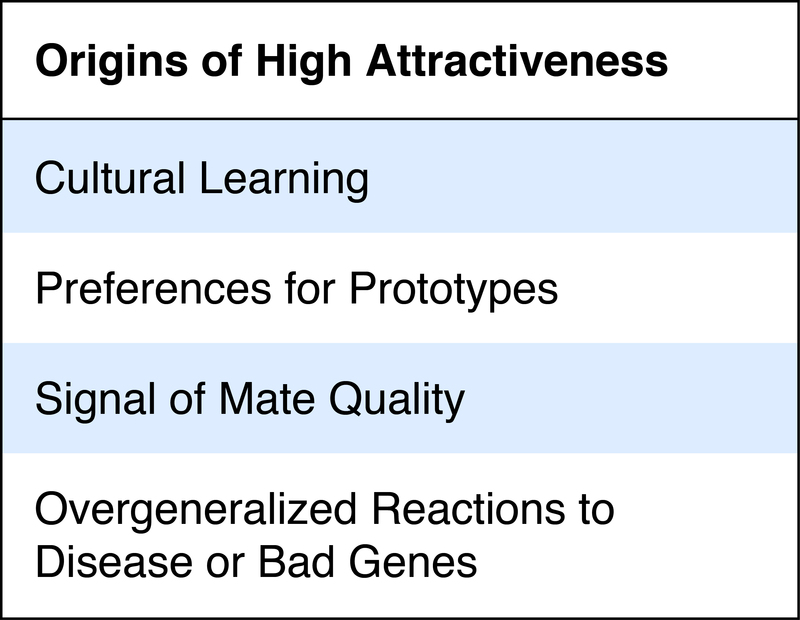

특정 사람들이 매력적으로 여겨지는 이유를 설명하기 위해 문화적, 인지적, 진화론적, 과잉 일반화 설명이 제시되었습니다. 초기 설명에 따르면 매력은 한 문화권에서 선호하는 것에 기반한다고 합니다. 이는 여러 문화권에서 매력을 전달하기 위해 사용하는 다양한 장식, 장신구, 신체 변형이 이를 뒷받침합니다.

예를 들어, 그림 1에 표시된 여성의 긴 목은 서양인에게는 매력적이라고 평가되지 않을 것입니다. 그러나 미얀마 전통 부족에서는 긴 목이 신화 속 용과 닮았다고 여겨져 긴 목을 선호해 왔습니다. 이와 같은 문화적 차이에도 불구하고 매력은 사회적 학습에 의한 것이라는 주장에 대한 강력한 증거가 연구 결과에 의해 제시되었습니다. 실제로 어린 유아는 덜 매력적이라고 판단된 얼굴보다 성인이 매우 매력적이라고 판단한 얼굴을 더 선호합니다(Kramer, Zebrowitz, San Giovanni, & Sherak, 1995; Langlois et al., 1987). 또한 생후 12개월 아동은 성인이 매력적이라고 판단한 가면보다 매력적이지 않다고 판단한 실물 같은 가면을 쓴 낯선 사람에게 미소를 짓거나 함께 놀아줄 가능성이 낮습니다(Langlois, Roggman, & Rieser-Danner, 1990). 또한 서구 문화로부터 고립된 아마존 열대우림의 사람들을 포함하여 다양한 문화권의 사람들이 같은 얼굴을 매력적으로 여기는 것으로 나타났습니다(Cunningham, Roberts, Barbee, Druen, & Wu, 1995; Zebrowitz et al. 2012). 반면에 신체적 매력에는 문화적 차이가 더 많이 존재합니다. 특히 다양한 문화권의 사람들은 매우 마르고 쇠약해 보이는 신체가 매력적이지 않다는 데 동의하는 반면, 무거운 신체에 대한 평가에는 더 많은 차이를 보입니다. 서유럽 문화권, 특히 사회경제적 지위가 낮은 문화권에서는 다른 국가에 비해 큰 신체를 더 부정적으로 바라봅니다(Swami et al., 2010). 또한 아프리카계 미국인이 유럽계 미국인보다 과체중 여성을 덜 가혹하게 판단한다는 증거도 있습니다(Hebl & Heatherton, 1997).

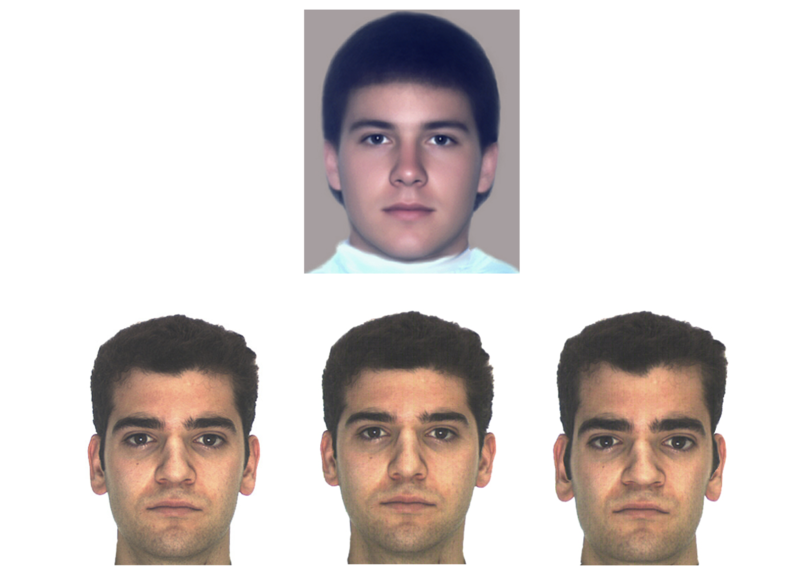

문화적 학습이 매력적이라고 생각하는 사람에 대해 어느 정도 기여하지만, 매력의 보편적 요소는 문화적으로 보편적인 설명이 필요합니다. 한 가지 제안은 매력은 익숙한 자극을 인식하고 선호하도록 이끄는 보다 일반적인 인지 메커니즘의 부산물이라는 것입니다. 사람들은 카테고리의 극단에 있는 것보다 카테고리의 원형, 즉 카테고리의 평균에 가까운 카테고리의 구성원을 선호합니다. 따라서 사람들은 사람의 얼굴이든, 자동차든, 동물이든 평균적인 자극을 더 매력적으로 느낍니다(Halberstadt, 2006). 실제로 많은 사람의 얼굴을 평균적으로 합성한 얼굴 모프는 개별 얼굴을 합성한 것보다 더 매력적입니다(Langlois & Roggman, 1990). 또한 평균 얼굴에 가깝게 변형된 개별 얼굴은 평균에서 멀어진 얼굴보다 더 매력적입니다(그림 2, Martinez & Benevente, 1998의 얼굴 참조). 범주 원형에 가까운 자극에 대한 선호는 우리가 남성적인 신체적 특성을 가진 남성과 여성적인 특성을 가진 여성을 더 선호한다는 사실과도 일치합니다. 이러한 선호도는 얼굴, 목소리 또는 신체에서 평균적이거나 전형적인 것은 우리가 본 사람에 따라 달라지기 때문에 가장 매력적인 사람은 우리의 학습 경험에 따라 달라진다는 것을 예측할 수 있습니다. 학습 경험의 효과에 따라 어린 유아는 새로운 얼굴의 평균인 모프보다 이전에 본 얼굴의 평균인 얼굴 모프를 선호합니다(Rubenstein, Kalakanis, & Langlois, 1999). 단기간의 지각 경험은 성인의 경우에도 매력 판단에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다. 동일한 왜곡이 있는 일련의 얼굴에 잠깐 노출되면 해당 왜곡이 있는 새로운 얼굴에 대한 평가된 매력이 증가하며(Rhodes, Jeffery, Watson, Clifford, & Nakayama, 2003), 인간과 침팬지 얼굴의 변형에 노출되면 약간의 침팬지 얼굴로 변형된 새로운 인간 얼굴에 대한 평가된 매력이 증가합니다(Principe & Langlois, 2012).

얼굴을 포함한 평균 자극이 선호되는 이유 중 하나는 분류하기 쉽고, 자극이 분류하기 쉬우면 긍정적인 감정을 이끌어내기 때문입니다(Winkielman, Halberstadt, Fazendeiro, & Catty, 2006). 평균 자극이 선호되는 또 다른 이유는 익숙한 자극에 대해 덜 불안해하기 때문일 수 있습니다(Zajonc, 2001). 다른 모든 것이 동일하다면, 우리는 새로운 자극보다 이전에 본 자극을 선호하며(단순 노출 효과), 이전에 본 자극과 유사한 자극을 선호하며(일반화된 단순 노출 효과), 또한 이전에 본 자극과 유사한 자극을 선호합니다(일반화된 단순 노출 효과). 불안감 감소 메커니즘과 일관되게, 다른 인종의 얼굴에 노출되면 참가자가 본 얼굴뿐만 아니라 익숙한 다른 인종 범주에 속하는 새로운 얼굴에 대해서도 부정적으로 평가되는 자극에 반응하는 영역의 신경 활성화가 감소했습니다(Zebrowitz & Zhang, 2012). 이러한 일반화된 단순 노출 효과는 매력성보다는 호감도 판단에 더 신뢰할 수 있지만, 더 친숙해 보이는 평균 자극에 대한 선호도도 설명할 수 있습니다(Rhodes, Halberstadt, & Brajkovich, 2001; Rhodes, Halberstadt, Jeffery, & Palermo, 2005). 분류의 용이성 때문이든 덜 불안하기 때문이든, 인지적 설명에 따르면 지각 학습으로 인해 특정 사람이 더 친숙해졌기 때문에 더 매력적이라는 것입니다.

특정 사람을 매력적으로 느끼는 이유에 대한 인지적 설명과 달리, 진화론적 설명은 그러한 사람을 선호하도록 적응했기 때문에 선호가 발전했다고 주장합니다. 보다 구체적으로, 좋은 유전자 가설은 평균성, 대칭성, 성 원형성, 젊음과 같은 신체적 특성을 가진 사람이 더 좋은 품질의 배우자이기 때문에 더 매력적이라는 가설을 제시합니다. 배우자의 자질은 더 나은 건강, 더 나은 생식력 또는 더 나은 유전적 특성을 반영하여 더 나은 자손으로 이어져 번식 성공률을 높일 수 있습니다(Thornhill & Gangestad, 1999). 이론적으로 평균성과 대칭성은 환경적 스트레스 요인에도 불구하고 정상적으로 발달할 수 있는 능력을 보여주기 때문에 유전적 적합성에 대한 증거를 제공합니다(Scheib, Gangestad, & Thornhill, 1999). 또한 평균성은 유전적 다양성을 나타내며(Thornhill & Gangestad, 1999), 이는 강력한 면역 체계와 관련이 있습니다(Penn, Damjanovich, & Potts, 2002). 남성 얼굴의 높은 남성성은 테스토스테론이 면역 체계에 가하는 스트레스를 견딜 수 있는 능력을 보여주기 때문에 건강함을 나타낼 수 있습니다(Folstad & Karter, 1992). 여성 얼굴의 높은 여성성은 성적 성숙도와 생식력을 나타내어 건강함을 나타낼 수 있습니다. 노화는 종종 인지 및 신체 기능의 저하와 생식력 감소와 관련이 있기 때문에 진화론적 설명은 젊음의 매력도 설명할 수 있습니다.

일부 연구자들은 얼굴의 매력과 건강 사이의 관계를 조사하여 매력성이 실제로 배우자의 질을 나타내는지 여부를 조사했습니다(Rhodes, 2006, 리뷰 참조). 이러한 관계에 대한 지지는 약합니다. 특히 매력, 평균성, 남성성(남성의 경우)이 매우 낮게 평가된 사람들은 이러한 자질이 평균인 사람들에 비해 건강이 좋지 않은 경향이 있습니다. 그러나 매력성, 평균성 또는 남성성이 높은 것으로 평가된 사람들은 평균적인 사람들과 차이가 없습니다(Zebrowitz & Rhodes, 2004). 과체중 또는 성별에 따른 허리 대 엉덩이 비율로 표시되는 낮은 신체 매력도는 여성의 건강 악화 또는 낮은 출산율과도 관련이 있을 수 있습니다(Singh & Singh, 2011). 지능이 높은 짝이 번식 성공률을 높일 수 있기 때문에 지능과의 관계를 조사하여 매력이 짝의 질을 나타내는지 평가한 연구도 있습니다. 특히, 지능이 높은 짝은 부모를 더 잘 돌볼 수 있습니다. 또한 지능은 유전되기 때문에 지능이 높은 짝은 더 지능적인 자손을 낳아 다음 세대에 유전자를 전달할 가능성이 더 높습니다(Miller & Todd, 1998). 매력은 지능과 양의 상관관계가 있다는 증거가 있습니다. 그러나 건강의 경우와 마찬가지로 그 관계는 약하며, 이는 매력도가 높은 사람들의 평균보다 높은 지능보다는 매력도가 매우 낮은 사람들의 평균보다 낮은 지능에 주로 기인하는 것으로 보입니다(Zebrowitz & Rhodes, 2004). 이러한 결과는 평균 매력도에서 미묘한 마이너스 편차가 낮은 체력을 나타낼 수 있다는 사실과 일치합니다. 예를 들어, 일반인이 유전적 기형으로 인식하기에는 너무 미묘한 사소한 얼굴 기형은 지능 저하와 관련이 있습니다(Foroud et al., 2012). 매력의 수준이 높지는 않지만 낮은 지능이나 건강에 대한 유효한 단서를 제공하지만, 매력은 어느 정도 타당성이 있는 범위에서도 이러한 특성에 대한 약한 예측 변수일 뿐이라는 점을 명심하는 것이 중요합니다.

매력도가 낮지만 높지 않은 것이 실제 특성을 진단할 수 있다는 사실은 우리가 특정 사람을 매력적으로 느끼는 이유에 대한 또 다른 설명과 일치합니다. 이를 변칙적 얼굴 과대 일반화라고 부르지만, 이는 변칙적 목소리나 신체에도 동일하게 적용될 수 있습니다. 진화론적 설명은 일반적으로 매력이 증가함에 따라 체력도 증가한다고 가정하고, 매우 매력적인 개인의 더 큰 체력, 즉 좋은 유전자 효과를 강조해 왔습니다(Buss, 1989). 이와는 대조적으로 과잉 일반화 가설은 매력의 수준이 낮은 체력에 대한 정확한 지표만을 제공한다고 주장합니다. 이 설명에 따르면 매력 후광 효과는 낮은 적합성에 대한 반응의 부산물입니다. 즉, 낮은 매력도를 평균보다 낮은 건강 및 지능의 지표로 사용하는 적응적 경향을 지나치게 일반화하고, 평균보다 높은 매력도를 평균보다 높은 건강 및 지능의 지표로 잘못 사용하는 것입니다(Zebrowitz & Rhodes, 2004). 과잉 일반화 가설은 또 다른 중요한 측면에서 진화 가설과 다릅니다. 이 가설은 짝을 선택할 때뿐만 아니라 다른 사회적 상호 작용에서도 낮은 체력을 감지하는 것이 중요하다는 것과 관련이 있습니다. 이는 매력 후광 효과가 여러 영역에서 존재한다는 사실과도 일치합니다.

매력에 대한 문화적, 인지적, 과잉 일반화 설명이 인상의 후광 효과를 반드시 정확하게 예측하는 것은 아니지만, 진화론적 "좋은 유전자" 설명은 예측할 수 있습니다. 앞서 살펴본 바와 같이, 이러한 예측을 어느 정도 뒷받침하는 근거가 있지만, 그 효과가 너무 약하고 제한적이어서 매우 매력적인 사람에 대한 강한 후광 효과를 완전히 설명하기에는 한계가 있습니다. 또한, 어떤 정확도가 있더라도 매력과 건강이나 지능과 같은 적응 특성 사이의 유전적 연관성을 반드시 의미하는 것은 아니라는 점을 인식하는 것이 중요합니다. 비유전적 메커니즘 중 하나는 환경적 요인의 영향입니다. 예를 들어, 사람이 섭취하는 영양의 질은 매력과 건강 모두의 발달에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다(Whitehead, Ozakinci, Stephen, & Perrett, 2012). 또 다른 비유전적 설명으로는 자기충족적 예언 효과(Snyder, Tanke, & Berscheid, 1977)가 있습니다. 예를 들어, 교사가 더 매력적인 학생에 대한 기대치가 높을수록 지능이 높아질 수 있으며, 이는 외모 이외의 이유로 교사가 높은 기대치를 가질 때 나타나는 효과입니다(Rosenthal, 2003).

*** Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version) ***

결론

불공평해 보일지 모르지만 매력은 많은 이점을 가져다줍니다. 더 매력적인 사람은 연애 파트너뿐만 아니라 부모, 또래, 교사, 고용주, 심지어 판사나 유권자에게도 더 선호됩니다. 또한, 다양한 문화권의 유아 및 인식자들이 비슷한 반응을 보이는 등 누가 매력적인지에 대한 상당한 일치점이 있습니다. 이는 문화적 영향이 매력을 완전히 설명할 수는 없지만, 경험이 영향을 미친다는 것을 시사합니다. 특정 사람이 우리에게 매력적인 이유에 대해서는 논란이 있습니다. 인지적 설명에서는 원형을 처리하기 쉽거나 익숙한 자극과 관련된 안전성이 더 높은 매력의 원인이라고 설명합니다. 진화론적 설명은 배우자를 선택할 때 더 나은 건강이나 유전적 적합성을 나타내는 신체적 특성을 선호하는 적응적 가치에 더 높은 매력을 부여합니다. 과잉 일반화 설명은 건강이 나쁘거나 유전적 체력이 낮다는 신호를 보내는 신체적 특성을 적응적으로 회피하기 위해 과잉 일반화하기 때문에 더 높은 매력을 느낀다고 설명합니다. 어떤 설명이 가장 좋은지에 대해서는 논란이 있지만, 제안된 모든 메커니즘이 어느 정도 타당성을 가질 수 있다는 점을 인식하는 것이 중요합니다.

Outside Resources

- Article: For Couples, Time Can Upend the Laws of Attraction - This is an accessible New York Times article, summarizing research findings that show romantic couples’ level of attractiveness is correlated if they started dating soon after meeting (predicted by the matching hypothesis). However, if they knew each other or were friends for a while before dating, they were less likely to match on physical attractiveness. This research highlights that while attractiveness is important, other factors such as acquaintanceship length can also be important.

- http://nyti.ms/1HtIkFt

- Article: Is Faceism Spoiling Your Life? - This is an accessible article that describes faceism, as well as how our expectations of people (based on their facial features) influence our reactions to them. It presents the findings from a few studies, such as how participants making snap judgments of political candidates’ faces predicted who won the election with almost 70% accuracy. It includes example photos of faces we would consider more or less competent, dominant, extroverted, or trustworthy.

- http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20150707-is-faceism-spoiling-your-life

- Video: Is Your Face Attractive? - This is a short video. The researcher in the video discusses and shows examples of face morphs, and then manipulates pictures of faces, making them more or less masculine or feminine. We tend to prefer women with more feminized faces and men with more masculine faces, and the video briefly correlates these characteristics to good health.

- http://www.discovery.com/tv-shows/other-shows/videos/science-of-sex-appeal-is-your-face-attractive/

- Video: Multiple videos realted to the science of beauty

- http://dsc.discovery.com/search.htm?terms=science+of+beauty

- Video: Multiple videos related to the science of sex appeal

- http://dsc.discovery.com/search.htm?terms=science+of+sex+appeal

- Video: The Beauty of Symmetry - A short video about facial symmetry. It describes facial symmetry, and explains why our faces aren’t always symmetrical. The video shows a demonstration of a researcher photographing a man and a woman and then manipulating the photos.

- http://www.discovery.com/tv-shows/other-shows/videos/science-of-sex-appeal-the-beauty-of-symmetry/

- Video: The Economic Benefits of Being Beautiful - Less than 2-minute video with cited statistics about the advantages of being beautiful. The video starts with information about how babies are treated differently, and it quickly cites 14 facts about the advantages of being attractive, including the halo effect.

Discussion Questions

- Why do you think the attractiveness halo exists even though there is very little evidence that attractive people are more intelligent or healthy?

- What cultural influences affect whom you perceive as attractive? Why?

- How do you think evolutionary theories of why faces are attractive apply in a modern world, where people are much more likely to survive and reproduce, regardless of how intelligent or healthy they are?

- Which of the theories do you think provides the most compelling explanation for why we find certain people attractive?

Vocabulary

- Anomalous face overgeneralization hypothesis

- Proposes that the attractiveness halo effect is a by-product of reactions to low fitness. People overgeneralize the adaptive tendency to use low attractiveness as an indicator of negative traits, like low health or intelligence, and mistakenly use higher-than-average attractiveness as an indicator of high health or intelligence.

- Attractiveness halo effect

- The tendency to associate attractiveness with a variety of positive traits, such as being more sociable, intelligent, competent, and healthy.

- Good genes hypothesis

- Proposes that certain physical qualities, like averageness, are attractive because they advertise mate quality—either greater fertility or better genetic traits that lead to better offspring and hence greater reproductive success.

- Mere-exposure effect

- The tendency to prefer stimuli that have been seen before over novel ones. There also is a generalized mere-exposure effect shown in a preference for stimuli that are similar to those that have been seen before.

- Morph

- A face or other image that has been transformed by a computer program so that it is a mixture of multiple images.

- Prototype

- A typical, or average, member of a category. Averageness increases attractiveness.

References

- Benson, P. L., Karabenick, S. A., & Lerner, R. M. (1976). Pretty pleases: The effects of physical attractiveness, race, and sex on receiving help. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 12, 409–415.

- Buss, D. M. (1989). Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 12, 1–49.

- Canning, H., & Mayer, J. (1966). Obesity—its possible effect on college acceptance. New England Journal of Medicine, 275, 1172–1174.

- Collins, S. A. (2000). Men's voices and women's choices. Animal Behaviour, 60, 773–780.

- Crandall, C. S. (1991). Do heavy-weight students have more difficulty paying for college? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17, 606–611.

- Cunningham, M. R. (1986). Measuring the physical in physical attractiveness: Quasi-experiments on the sociobiology of female facial beauty. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 925–935.

- Cunningham, M. R., Roberts, A. R., Barbee, A. P., Druen, P. B., & Wu, C. (1995). 'Their ideas of beauty are, on the whole, the same as ours': Consistency and variability in the cross-cultural perception of female physical attractiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 261–279.

- Dipboye, R. L., Arvey, R. D., & Terpstra, D. E. (1977). Sex and physical attractiveness of raters and applicants as determinants of résumé evaluations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 62, 288–294.

- Eagly, A. H., Ashmore, R. D., Makhijani, M. G., & Longo, L. C. (1991). What is beautiful is good, but . . . : A meta-analytic review of research on the physical attractiveness stereotype. Psychological Bulletin, 110, 109–128.

- Feingold, A. (1990). Gender differences in effects of physical attractiveness on romantic attraction: A comparison across five research paradigms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 981–993.

- Feingold, A. (1988). Matching for attractiveness in romantic partners and same-sex friends: A meta-analysis and theoretical critique. Psychological Bulletin, 104, 226–235.

- Folstad, I., & Karter, A. J. (1992). Parasites, bright males, and the immunocompetence handicap. American Naturalist, 139, 603–622.

- Foroud, T. W., Wetherill, L., Vinci-Booher, S., Moore, E. S., Ward, R. E., Hoyme, H. E…. Jacobson, S. W. (2012). Relation over time between facial measurements and cognitive outcomes in fetal alcohol-exposed children. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 36, 1634–1646.

- Franklin, R. G., Jr., & Adams, R. B., Jr. (2010). The two halves of beauty: Laterality and the duality of facial attractiveness. Brain and Cognition, 72, 300–305.

- Franklin, R. G., Jr., & Adams, R. B., Jr. (2009). A dual-process account of female facial attractiveness preferences: Sexual and nonsexual routes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 1156–1159.

- Gregory, S. W., & Gallagher, T. J. (2002). Spectral analysis of candidates' nonverbal vocal communication: Predicting U.S. presidential election outcomes. Social Psychology Quarterly, 65, 298–308.

- Gross, A. E., & Crofton, C. (1977). What is good is beautiful. Sociometry, 40, 85–90.

- Halberstadt, J. B. (2006). The generality and ultimate origins of the attractiveness of prototypes. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10, 166–183.

- Hamermesh, D. S., & Biddle, J. E. (1994). Beauty and the labor market. American Economic Review, 84, 1174–1194.

- Hebl, M., & Heatherton, T. F. (1997). The stigma of obesity: The differences are black and white. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24, 417–426.

- Hildebrandt, K. A., & Fitzgerald, H. E. (1979). Facial feature determinants of perceived infant attractiveness. Infant Behavior and Development, 2, 329–339.

- Hosoda, M., Stone-Romero, E. F., & Coats, G. (2003). The effects of physical attractiveness on job-related outcomes: A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Personnel Psychology, 56, 431-462.

- Kramer, S., Zebrowitz, L. A., San Giovanni, J. P., & Sherak, B. (1995). Infants' preferences for attractiveness and babyfaceness. In B. G. Bardy, R. J. Bootsma, & Y. Guiard (Eds.), Studies in Perception and Action III (pp. 389–392). Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum.

- Langlois, J. H., & Roggman, L. A. (1990). Attractive faces are only average. Psychological Science, 1, 115–121.

- Langlois, J. H., Kalakanis, L., Rubenstein, A. J., Larson, A., Hallam, M., & Smoot, M. (2000). Maxims or myths of beauty? A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 390–423.

- Langlois, J. H., Roggman, L. A., & Rieser-Danner, L. A. (1990). Infants’ differential social responses to attractive and unattractive faces. Developmental Psychology, 26(1), 153–159.

- Langlois, J. H., Roggman, L. A., Casey, R. J., Ritter, J. M., Rieser-Danner, L. A., & Jenkins, V. Y. (1987). Infant preferences for attractive faces: Rudiments of a stereotype? Developmental Psychology, 23, 363–369.

- Larkin, J. C., & Pines, H. A. (1979). No fat persons need apply: Experimental studies of the overweight stereotype and hiring preference. Work and Occupations, 6, 312–327.

- Little, A. C., Jones, B. C., Penton-Voak, I. S., Burt, D. M., & Perrett, D. I. (2002). Partnership status and the temporal context of relationships influence human female preferences for sexual dimorphism in male face shape. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B, 269, 1095–1100.

- Martinez, A. M., & Benavente, R. (1998). The AR face database, CVC Tech. Report #24.

- Miller, G. F., & Todd, P. M. (1998). Mate choice turns cognitive. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 2, 190–198.

- Miyake, K., & Zuckerman, M. (1993). Beyond personality impressions: Effects of physical and vocal attractiveness on false consensus, social comparison, affiliation, and assumed and perceived similarity. Journal of Personality, 61, 411–437.

- Montoya, R. M. (2008). I'm hot, so I'd say you're not: The influence of objective physical attractiveness on mate selection. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 1315–1331.

- Mueller, U., & Mazur, A. (1996). Facial dominance of West Point cadets as a predictor of later military rank. Social Forces, 74, 823–850.

- Nisbett, R. E., & Wilson, T. D. (1977). Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes. Psychological Review, 84, 231–259.

- Penn, D. J., Damjanovich, K., & Potts, W. K. (2002). MHC heterozygosity confers a selective advantage against multiple-strain infections. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99, 11260–11264.

- Principe, C. P., & Langlois, J. H. (2012). Shifting the prototype: Experience with faces influences affective and attractiveness preferences. Social Cognition, 30, 109–120.

- Puts, D. A., Barndt, J. L., Welling, L. L., Dawood, K., & Burriss, R. P. (2011). Intrasexual competition among women: Vocal femininity affects perceptions of attractiveness and flirtatiousness. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 111–115.

- Rhodes, G. (2006). The evolutionary psychology of facial beauty. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 199–226.

- Rhodes, G., Halberstadt, J., & Brajkovich, G. (2001) Generalization of mere-exposure effects to averaged composite faces. Social Cognition, 19, 57–70.

- Rhodes, G., Halberstadt, J., Jeffery, L., & Palermo, R. (2005). The attractiveness of average faces is not a generalized mere-exposure effect. Social Cognition, 23, 205–217.

- Rhodes, G., Jeffery, L., Watson, T. L., Clifford, C. W. G., & Nakayama, K. (2003) Fitting the mind to the world: Face adaptation and attractiveness aftereffects. Psychological Science, 14, 558–566.

- Rhodes, G. Simmons, L. W. Peters, M. (2005). Attractiveness and sexual behavior: Does attractiveness enhance mating success? Evolution and Human Behavior, 26, 186–201

- Richardson, S. A., Goodman, N., Hastorf, A. H., & Dornbusch, S.M. (1961). Cultural uniformity in reaction to physical disabilities. American Sociology Review, 26, 241–247.

- Riggio, R. E., & Friedman, H. S. (1986). Impression formation: The role of expressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 421–427.

- Riggio, R. E., Widaman, K. F., Tucker, J. S., & Salinas, C. (1991). Beauty is more than skin deep: Components of attractiveness. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 12, 423–439.

- Rosenthal, R. (2003). Covert communication in laboratories, classrooms, and the truly real world. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12, 151–154.

- Rubenstein, A. J., Kalakanis, L., & Langlois, J. H. (1999). Infant preferences for attractive faces: A cognitive explanation. Developmental Psychology, 35, 848–855.

- Scheib, J. E., Gangestad, S. W., & Thornhill, R. (1999). Facial attractiveness, symmetry, and cues of good genes. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 266, 1913–1917.

- Singh, D., & Singh, D. (2011). Shape and significance of feminine beauty: An evolutionary perspective. Sex Roles, 64, 723–731.

- Snyder, M., Tanke, E. D., & Berscheid, E. (1977). Social perception and interpersonal behavior: On the self-fulfilling nature of social stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35, 655–666.

- Sternglanz, S. H., Gray, J. L., & Murakami, M. (1977). Adult preferences for infantile facial features: An ethological approach. Animal Behaviour, 25, 108–115.

- Stewart, J. E. (1980). Defendant's attractiveness as a factor in the outcome of criminal trials: An observational study. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 10, 348–361.

- Swami, V., Furnham, A., Chamorro-Premuzic, T., Akbar, K., Gordon, N., Harris, T., . . . Tovée, M. J. (2010). More than just skin deep? Personality information influences men's ratings of the attractiveness of women's body sizes. The Journal of Social Psychology, 150, 628–647.

- Thornhill, R., & Gangestad, S. W. (1999). Facial attractiveness. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 3, 452–460.

- Tigue, C. C., Borak, D. J., O'Connor, J. J. M., Schandl, C., & Feinberg, D. R. (2012). Voice pitch influences voting behavior. Evolution and Human Behavior, 33, 210–216.

- Verhulst, B., Lodge, M., & Lavine, H. (2010). The attractiveness halo: Why some candidates are perceived more favorably than others. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 34, 111–117.

- Walster, E., Aronson, V., Abrahams, D., & Rottman, L. (1966). Importance of physical attractiveness in dating behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4, 508–516.

- Whitehead, R. D., Ozakinci, G., Stephen, I. D., & Perrett, D. I. (2012). Appealing to vanity: Could potential appearance improvement motivate fruit and vegetable consumption? American Journal of Public Health, 102, 207–211.

- Winkielman, P., Halberstadt, J., Fazendeiro, T., & Catty, S. (2006). Prototypes are attractive because they are easy on the mind. Psychological Science, 17, 799–806.

- Zajonc, R. B. (2001). Mere exposure: A gateway to the subliminal. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 224–228.

- Zebrowitz, L. A., & Zhang, E., (2012). Neural evidence for reduced apprehensiveness of familiarized stimuli in a mere exposure paradigm. Social Neuroscience, 7, 347–358.

- Zebrowitz, L. A. & Rhodes, G. (2004). Sensitivity to “bad genes” and the anomalous face overgeneralization effect: Accuracy, cue validity, and cue utilization in judging intelligence and health. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 28, 167–185.

- Zebrowitz, L. A., Wang, R., Bronstad, P. M., Eisenberg, D., Undurraga, E., Reyes-García, V., & Godoy, R., (2012). First impressions from faces among U.S. and culturally isolated Tsimane’ people in the Bolivian rainforest. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 43, 119–134.

- Zuckerman, M., & Driver, R. E. (1989). What sounds beautiful is good: The vocal attractiveness stereotype. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 13, 67–82.

Authors

Robert G. FranklinRobert G. Franklin is an Assistant Professor of Psychology at Anderson University. He has authored several publications investigating which features contribute to attractiveness judgments and how attractiveness affects first impressions.

Robert G. FranklinRobert G. Franklin is an Assistant Professor of Psychology at Anderson University. He has authored several publications investigating which features contribute to attractiveness judgments and how attractiveness affects first impressions. Leslie ZebrowitzLeslie Zebrowitz, Manuel Yellen Professor of Social Relations at Brandeis University, has authored three books and many publications on physical appearance stereotypes. Recipient of an NIH Career Development Award for social neuroscience, she is currently supported by an NIA grant investigating the mechanisms influencing age-related changes in face impression accuracy.

Leslie ZebrowitzLeslie Zebrowitz, Manuel Yellen Professor of Social Relations at Brandeis University, has authored three books and many publications on physical appearance stereotypes. Recipient of an NIH Career Development Award for social neuroscience, she is currently supported by an NIA grant investigating the mechanisms influencing age-related changes in face impression accuracy.

Creative Commons License

Attraction and Beauty by Robert G. Franklin and Leslie Zebrowitz is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

Attraction and Beauty by Robert G. Franklin and Leslie Zebrowitz is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.