감정 신경 과학(Affective Neuroscience)

감정 신경 과학

By Eddie Harmon-Jones and Cindy Harmon-JonesUniversity of New South Wales

이 모듈에서는 감정의 신경과학에 대한 간략한 개요를 제공합니다. 인간과 동물의 연구 결과를 통합하여 기본적인 정서 시스템에 관여하는 뇌 네트워크와 관련 신경전달물질을 설명합니다.

학습 목표

- Define affective neuroscience.

- Describe neuroscience techniques used to study emotions in humans and animals.

- Name five emotional systems and their associated neural structures and neurotransmitters.

- Give examples of exogenous chemicals (e.g., drugs) that influence affective systems, and discuss their effects.

- Discuss multiple affective functions of the amygdala and the nucleus accumbens.

- Name several specific human emotions, and discuss their relationship to the affective systems of nonhuman animals.

정서 신경 과학을 정의합니다.

인간과 동물의 감정을 연구하는 데 사용되는 신경 과학 기법을 설명합니다.

다섯 가지 정서 시스템과 그와 관련된 신경 구조 및 신경 전달 물질의 이름을 말하십시오.

정서 시스템에 영향을 미치는 외인성 화학 물질(예: 약물)의 예를 제시하고 그 효과에 대해 토론하십시오.

편도체와 편도체핵의 여러 정서적 기능에 대해 논하십시오.

인간의 특정 감정을 몇 가지 거론하고, 그 감정이 비인간 동물의 정서 체계와 어떤 관계가 있는지 토론하십시오.

정서 신경과학: 정동 신경과학이란 무엇인가요?

정서 신경과학은 뇌가 어떻게 정서적 반응을 일으키는지 연구합니다. 정서는 신체의 변화(예: 얼굴 표정), 자율 신경계 활동의 변화, 느낌 상태(주관적 반응), 특정 방식으로 행동하려는 충동(동기; Izard, 2010)을 포함하는 심리적 현상입니다. 정서 신경과학은 물질(뇌 구조와 화학 물질)이 마음의 가장 흥미로운 측면 중 하나인 감정을 어떻게 만들어내는지 이해하는 것을 목표로 합니다. 정서 신경과학은 감정의 중요성에 대해 다른 과학 분야와 일반인에게 신뢰할 수 있는 증거를 제공하는 편향되지 않고 관찰 가능한 측정 방법을 사용합니다. 또한 정서 장애(예: 우울증)에 대한 생물학적 기반 치료법으로 이어집니다.

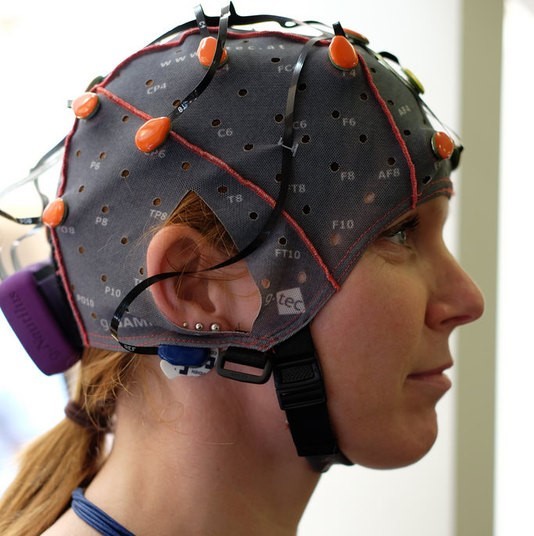

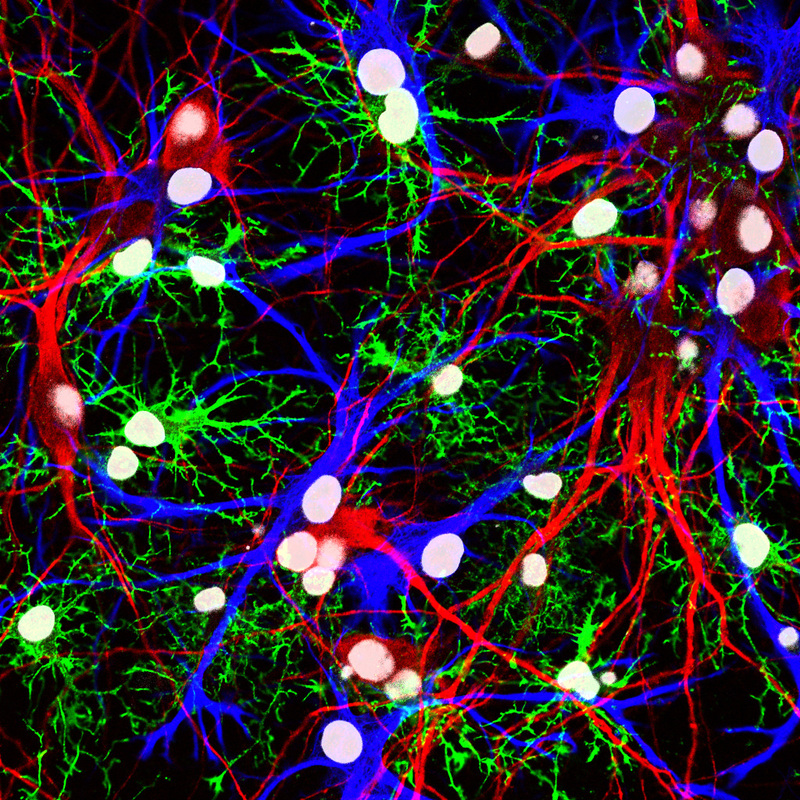

인간의 뇌와 감정을 포함한 반응은 복잡하고 유연합니다. 이에 비해 인간이 아닌 동물은 신경계가 더 단순하고 기본적인 감정 반응이 더 많습니다. 전극 이식, 병변 치료, 호르몬 투여와 같은 침습적 신경과학 기술은 인간보다 동물에게 더 쉽게 사용될 수 있습니다. 인간의 신경과학은 주로 뇌파 검사(EEG) 및 기능적 자기공명영상(fMRI)과 같은 비침습적 기술과 사고나 질병으로 인한 뇌 병변을 가진 개인에 대한 연구에 의존해야 합니다. 따라서 동물 연구는 인간의 정서적 과정을 이해하는 데 유용한 모델을 제공합니다. 다른 종, 특히 쥐, 개, 원숭이와 같은 사회적 포유류에서 발견되는 정서 회로는 인간의 정서 네트워크와 유사하게 작동하지만, 비인간 동물의 뇌는 더 기본적인 기능을 합니다.

인간의 경우 감정과 이와 관련된 신경계는 더 복잡하고 유연한 계층을 가지고 있습니다. 동물에 비해 인간은 매우 다양하고 미묘하며 때로는 상충하는 감정을 경험합니다. 또한 인간은 이러한 감정에 복잡한 방식으로 반응하며, 의식적인 목표, 가치관, 기타 인지가 감정적 반응 외에도 행동에 영향을 미칩니다. 하지만 이 모듈에서는 차이점보다는 유기체 간의 유사점에 초점을 맞춥니다. 우리는 종종 감정을 경험하거나 특정 신경 활성화의 증거를 보이는 개인을 지칭할 때 "유기체"라는 용어를 사용합니다. 유기체에는 쥐, 원숭이 또는 인간이 포함될 수 있습니다.

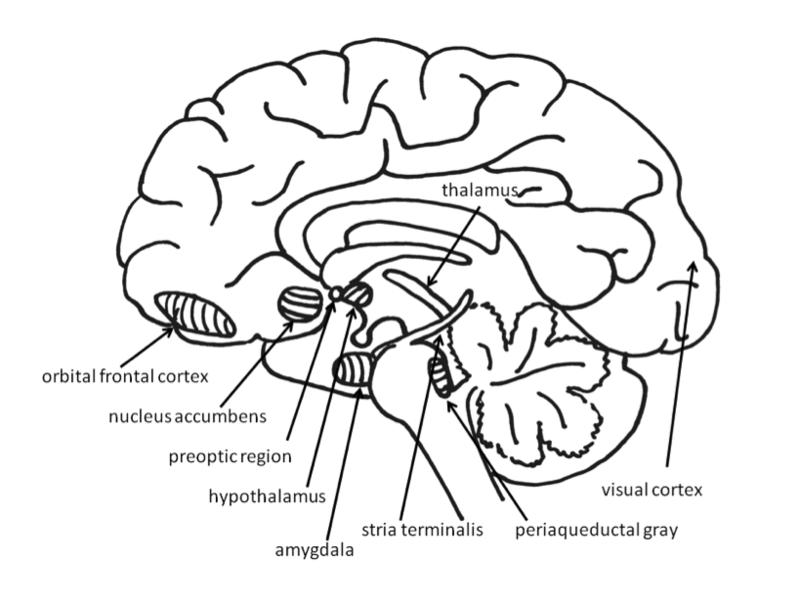

모든 종에 걸쳐 감정 반응은 유기체의 생존과 번식 욕구를 중심으로 조직화되어 있습니다. 감정은 지각, 인지, 행동에 영향을 미쳐 유기체가 생존하고 번성하는 데 도움을 줍니다(Farb, Chapman, & Anderson, 2013). 뇌의 구조 네트워크는 서로 다른 욕구에 반응하며, 서로 다른 감정 간에 일부 겹치는 부분이 있습니다. 특정 감정은 뇌의 단일 구조에 위치하지 않습니다. 대신, 감정 반응은 활성화 네트워크와 관련이 있으며, 어떤 감정 과정 중에 뇌의 많은 부분이 활성화됩니다. 실제로 감정 반응에 관여하는 뇌 회로는 거의 뇌 전체를 포함합니다(Berridge & Kringelbach, 2013). 대뇌 피질 아래 뇌 깊숙한 곳에 위치한 뇌 회로는 주로 기본적인 감정을 생성하는 역할을 합니다(Berridge & Kringelbach, 2013; Panksepp & Biven, 2012). 과거에는 여기에서 검토할 특정 뇌 구조에 대한 연구가 집중되었지만, 향후 연구에서는 이러한 과정에서 뇌의 다른 영역도 중요하다는 사실이 밝혀질 수 있습니다.

기본 감정

욕망: 보상을 추구하는 신경계

가장 중요한 정서 신경계 중 하나는 욕구 또는 보상에 대한 식욕과 관련이 있습니다. 연구자들은 이러한 식욕 과정을 "원함"(Berridge & Kringelbach, 2008), "추구"(Panksepp & Biven, 2012) 또는 "행동 활성화 민감도"(Gray, 1987)와 같은 용어를 사용하여 언급합니다. 식욕 시스템이 활성화되면 유기체는 열정, 관심, 호기심을 보입니다. 이러한 신경 회로는 동물이 식욕을 돋우는 음식, 매력적인 섹스 파트너 및 기타 즐거운 자극과 같은 보상을 찾아 환경을 탐색하도록 동기를 부여합니다. 식욕 시스템이 약해지면 유기체는 우울하고 무력한 모습을 보입니다.

이 시스템과 관련된 구조에 대한 많은 증거는 직접 뇌 자극을 사용한 동물 연구에서 나옵니다. 시상하부 측면 또는 시상하부와 연결된 피질 또는 중뇌 영역에 전극을 이식하면 동물은 레버를 눌러 전기 자극을 전달하며, 이는 자극을 쾌적하게 느낀다는 것을 나타냅니다. 욕구 시스템의 영역에는 편도체, 편도체핵, 전두엽 피질도 포함됩니다(Panksepp & Biven, 2012). 중변연계 및 중피질 도파민 회로에서 생성되는 신경전달물질인 도파민은 이러한 영역을 활성화합니다. 도파민은 흥분, 의미, 기대감을 만들어냅니다. 이러한 구조는 도파민과 유사한 효과를 내는 화학물질인 코카인이나 암페타민과 같은 약물에도 민감합니다(Panksepp & Biven, 2012).

인간과 비인간 동물을 대상으로 한 연구에 따르면 좌측 전전두피질(우측 전전두피질에 비해)은 욕망과 흥미와 같은 식욕적인 감정을 느낄 때 더 활발하게 활동하는 것으로 나타났습니다. 연구자들은 먼저 좌측 전전두피질에 손상을 입은 사람은 우울증에 걸리는 반면, 우측 전전두피질에 손상을 입은 사람은 조증에 걸린다는 사실에 주목했습니다(Goldstein, 1939). 좌측 전두엽 활성화와 접근 관련 감정 사이의 관계는 뇌파 및 fMRI를 사용하여 건강한 개인에서 확인되었습니다(Berkman & Lieberman, 2010). 예를 들어, 생후 2~3일 된 영아에게 자당을 혀 위에 올려놓았을 때 좌측 전두엽 활성화가 증가하고(Fox & Davidson, 1986), 배고픈 성인이 바람직한 디저트 사진을 볼 때 좌측 전두엽 활성화가 증가합니다(Gable & Harmon-Jones, 2008). 또한 식욕 상황에서 좌측 전두엽 활동이 활발해지는 것은 도파민과 관련이 있는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다(Wacker, Mueller, Pizzagalli, Hennig, & Stemmler, 2013).

"좋아요": 쾌락과 즐거움의 신경 회로

놀랍게도 개인이 보상에 대해 느끼는 욕망의 정도는 보상을 얼마나 좋아하는지와 일치할 필요는 없습니다. 보상의 즐거움과 관련된 신경 구조는 보상에 대한 욕구와 관련된 신경 구조와 다르기 때문입니다. '좋아함'(예: 달콤한 액체에 대한 즐거움)은 아기와 비인간 동물에서 핥는 속도, 혀 돌출, 행복한 표정을 측정하여 측정할 수 있는 반면, '원함'(욕구)은 보상을 얻기 위해 열심히 노력하려는 의지로 나타납니다(Berridge & Kringelbach, 2008). 약물 남용과 같은 주제에 대한 연구에서 좋아요는 원함과 구별되었습니다. 예를 들어, 마약 중독자는 사용 가능한 마약이 쾌락을 제공하지 않는다는 것을 알면서도 마약을 원하는 경우가 많습니다(Stewart, de Wit, & Eikelboom, 1984).

호감도에 대한 연구는 중격핵 내의 작은 영역과 복측 구개체의 후방 절반에 집중되어 있습니다. 이러한 뇌 영역은 오피오이드와 체내 칸나비노이드에 민감합니다. 보상 시스템의 다른 영역을 자극하면 욕구는 증가하지만 선호도는 증가하지 않으며 경우에 따라 선호도가 감소하기도 합니다. 욕망과 쾌락의 차이에 대한 연구는 인간 중독, 특히 습관화로 인해 더 이상 보상을 얻음으로써 쾌락을 느끼지 못하더라도 코카인, 아편, 도박 또는 섹스와 같은 보상을 계속해서 광적으로 추구하는 이유를 이해하는 데 기여합니다.

쾌락의 경험은 안와전두피질과도 관련이 있습니다. 이 영역의 뉴런은 원숭이가 바람직한 음식을 맛보거나 단순히 사진을 볼 때 활성화됩니다. 인간의 경우 이 영역은 돈, 기분 좋은 냄새, 매력적인 얼굴과 같은 유쾌한 자극에 의해 활성화됩니다(Gottfried, O'Doherty & Dolan, 2002; O'Doherty, Deichmann, Critchley, & Dolan, 2002; O'Doherty, Kringelbach, Rolls, Hornak, & Andrews, 2001; O'Doherty, Winston, Critchley, Perrett, Burt, & Dolan, 2003).

공포: 얼어붙고 도망치는 신경계

두려움은 잠재적으로 해로운 상황을 피하도록 동기를 부여하는 불쾌한 감정입니다. 뇌의 공포 관련 부위를 약간만 자극해도 동물은 얼어붙고, 강한 자극을 받으면 도망치게 됩니다. 공포 회로는 중뇌의 편도체에서 중뇌의 회색질 주변으로 확장됩니다. 이러한 구조는 글루타메이트, 코르티코트로핀 방출 인자, 부신피질자극호르몬, 콜레시스토키닌 및 여러 가지 신경 펩티드에 민감합니다. 벤조디아제핀 및 기타 진정제는 이러한 영역의 활성화를 억제합니다(Panksepp & Biven, 2012).

공포 반응에서 편도체의 역할은 광범위하게 연구되어 왔습니다. 아마도 공포가 생존에 매우 중요하기 때문에 두 가지 경로가 감각 기관에서 편도체로 신호를 보내기 때문일 것입니다. 예를 들어 뱀을 볼 때 감각 정보는 눈에서 시상으로 이동한 다음 시각 피질로 전달됩니다. 시각 피질은 편도체로 정보를 전달하여 공포 반응을 유발합니다. 그러나 시상도 정보를 편도체로 빠르게 전달하여 유기체가 뱀을 의식적으로 인지하기 전에 반응할 수 있도록 합니다(LeDoux, Farb, & Ruggiero, 1990). 시상에서 편도체까지의 경로는 빠르지만 시각 피질에서 편도체까지의 느린 경로보다 정확도가 떨어집니다. 편도체 또는 복측 해마 영역의 손상은 인간과 비인간 동물 모두의 공포 조절을 방해합니다(LeDoux, 1996).

분노: 분노와 공격의 회로

분노 또는 분노는 유기체가 접근하고 공격하도록 동기를 부여하는 흥분되고 불쾌한 감정입니다(Harmon-Jones, Harmon-Jones, & Price, 2013). 분노는 목표 좌절, 신체적 고통 또는 신체적 제약을 통해 유발될 수 있습니다. 영역 동물의 경우, 낯선 사람이 자신의 영역에 침입하면 분노가 유발됩니다(Blanchard & Blanchard, 2003). 분노와 두려움에 대한 신경망은 서로 가까이 있지만 분리되어 있습니다(Panksepp & Biven, 2012). 이 신경망은 내측 편도체에서 시상하부의 특정 부위를 거쳐 중뇌의 회색질 주변으로 확장됩니다. 분노 회로는 식욕 회로와 연결되어 있어 기대하는 보상이 부족하면 분노를 유발할 수 있습니다. 또한 인간은 분노할 때 좌측 전두엽 피질 활성화가 증가하여 분노가 접근과 관련된 감정이라는 생각을 뒷받침합니다(Harmon-Jones 외., 2013). 분노에 관여하는 신경전달물질은 아직 잘 알려져 있지 않지만, 물질 P가 중요한 역할을 할 수 있습니다(Panksepp & Biven, 2012). 분노에 관여할 수 있는 다른 신경 화학 물질로는 테스토스테론(Peterson & Harmon-Jones, 2012)과 아르기닌-바소프레신(Heinrichs, von Dawans, & Domes, 2009) 등이 있습니다. 오피오이드와 클로르프로마진 같은 고용량의 항정신병 약물을 포함한 여러 화학 물질이 분노 시스템을 억제합니다(Panksepp & Biven, 2012).

사랑: 보살핌과 애착의 신경계

인간과 같은 사회적 동물의 경우, 같은 종의 다른 구성원과의 애착은 사랑, 따뜻한 감정, 애정 등 애착이라는 긍정적인 감정을 불러일으킵니다. 양육 행동에 동기를 부여하는 감정(예: 모성애)은 보살핌과 보호를 받기 위해 애착 대상과 가까이 지내는 행동(예: 유아 애착)에 동기를 부여하는 감정과 구별됩니다. 모성 양육에 중요한 영역으로는 등쪽 전안부(Numan & Insel, 2003)와 선조체의 기저핵(Panksepp, 1998)이 있습니다. 이 영역은 성적 욕망과 관련된 영역과 겹치며 옥시토신, 아르기닌-바소프레신, 내인성 오피오이드(엔도르핀 및 엔케팔린) 등 동일한 신경전달물질에 민감합니다.

슬픔: 외로움과 공황의 신경 네트워크

유아 애착과 관련된 신경망은 분리에도 민감합니다. 이 영역은 슬픔, 공포, 외로움이라는 고통스러운 감정을 생성합니다. 유아 인간이나 다른 유아 포유류는 어미로부터 분리되면 조난 발성 또는 울음소리를 냅니다. 애착 회로는 전기적 자극을 받으면 유기체가 조난 발성을 내도록 하는 회로입니다.

애착 시스템은 신체적 통증 반응을 일으키는 부위와 매우 가까운 중뇌 피질 회색질에서 시작되며, 이는 통증 회로에서 시작되었을 수 있음을 시사합니다(Panksepp, 1998). 분리 고통은 또한 배측 시상, 복측 중격, 등쪽 전두엽 영역 및 선조체의 기저핵 영역(성 및 모성 회로 근처)을 자극함으로써 유발될 수 있습니다(Panksepp, Normansell, Herman, Bishop, & Crepeau, 1988).

이 영역은 내인성 오피오이드, 옥시토신, 프로락틴에 민감합니다. 이러한 신경전달물질은 모두 분리 장애를 예방합니다. 모르핀과 헤로인, 니코틴과 같은 아편성 약물은 긍정적인 사회적 상호작용에서 일반적으로 느껴지는 것과 유사한 쾌감과 만족감을 인위적으로 만들어냅니다. 이것이 이러한 약물이 중독성이 있는 이유를 설명할 수 있습니다. 공황 발작은 애착 체계에 의해 유발되는 격렬한 형태의 분리 불안으로 보이며, 공황은 아편제로 효과적으로 완화될 수 있습니다. 테스토스테론은 또한 애착 욕구를 감소시킴으로써 분리 장애를 감소시킵니다. 이와 일관되게 공황 발작은 남성보다 여성에게 더 흔합니다.

가소성: 경험은 뇌를 변화시킬 수 있습니다

특정 신경 영역의 반응은 경험에 의해 수정될 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 전대상핵의 앞쪽 껍질은 일반적으로 식욕과 같은 식욕 행동에 관여하고, 뒤쪽 껍질은 일반적으로 두려운 방어 행동에 관여합니다(Reynolds & Berridge, 2001, 2002). 인간의 신경 영상을 이용한 연구에서도 이러한 앞뒤 핵의 기능에 대한 구분이 밝혀졌습니다(Seymour, Daw, Dayan, Singer, & Dolan, 2007). 그러나 쥐가 스트레스가 많은 환경에 노출되면 공포를 유발하는 영역이 앞쪽으로 확장되어 거의 90%의 핵을 채웁니다. 반면, 쥐가 선호하는 집 환경에 노출되면 공포를 유발하는 영역이 축소되고 식욕을 유발하는 영역이 뒤쪽으로 확장되어 껍질의 약 90%를 채웁니다(Reynolds & Berridge, 2008).

뇌 구조에는 다양한 기능이 있습니다.

많은 정서 신경과학 연구에서 편도체와 편도체핵과 같은 전체 구조를 강조해 왔지만, 이러한 구조의 대부분은 복합체라고 부르는 것이 더 정확하다는 점에 유의하는 것이 중요합니다. 여기에는 서로 다른 작업을 수행하는 별개의 핵 그룹이 포함됩니다. 현재 fMRI와 같은 인간의 신경 영상 기술은 침습적 동물 신경과학이 할 수 있는 방식으로 개별 핵의 활동을 검사할 수 없습니다. 예를 들어, 비인간 영장류의 편도체는 13개의 핵과 피질 영역으로 나눌 수 있습니다(Freese & Amaral, 2009). 편도체의 이러한 영역은 서로 다른 기능을 수행합니다. 중핵은 선천적인 감정 표현과 관련 생리적 반응을 일으키는 뇌간 영역과 관련된 출력을 보냅니다. 기저핵은 안전을 향해 달리는 것과 같은 행동에 관여하는 선조체 영역과 연결되어 있습니다. 또한, 감정을 뇌 영역에 일대일로 매핑하는 것은 불가능합니다. 예를 들어, 편도체가 두려움에 관여하는 것에 대한 광범위한 연구가 진행되었지만, 편도체가 불확실성(Whalen, 1998)과 긍정적 감정(Anderson et al., 2003; Schulkin, 1990) 동안에도 활성화된다는 연구 결과도 있습니다.

결론

정서 신경과학 연구는 감정, 동기 부여, 행동 과정에 관한 지식에 기여해 왔습니다. 비인간 동물의 기본 감정 시스템에 대한 연구는 보다 복잡한 인간 감정의 조직과 발달에 대한 정보를 제공합니다. 아직 밝혀내야 할 것이 많지만, 정서 신경과학의 최신 연구 결과는 약물 사용과 남용, 공황장애와 같은 심리적 장애, 욕망과 즐거움, 슬픔과 사랑 같은 복잡한 인간 감정에 대한 이해에 이미 영향을 미쳤습니다.

Outside Resources

- Video: A 1-hour interview with Jaak Panksepp, the father of affective neuroscience

- Video: A 15-minute interview with Kent Berridge on pleasure in the brain

- Video: A 5-minute interview with Joseph LeDoux on the amygdala and fear

- Web: Brain anatomy interactive 3D model

- http://www.pbs.org/wnet/brain/3d/index.html

Discussion Questions

- The neural circuits of “liking” are different from the circuits of “wanting.” How might this relate to the problems people encounter when they diet, fight addictions, or try to change other habits?

- The structures and neurotransmitters that produce pleasure during social contact also produce panic and grief when organisms are deprived of social contact. How does this contribute to an understanding of love?

- Research shows that stressful environments increase the area of the nucleus accumbens that is sensitive to fear, whereas preferred environments increase the area that is sensitive to rewards. How might these changes be adaptive?

Vocabulary

- Affect

- An emotional process; includes moods, subjective feelings, and discrete emotions.

- Amygdala

- Two almond-shaped structures located in the medial temporal lobes of the brain.

- Hypothalamus

- A brain structure located below the thalamus and above the brain stem.

- Neuroscience

- The study of the nervous system.

- Nucleus accumbens

- A region of the basal forebrain located in front of the preoptic region.

- Orbital frontal cortex

- A region of the frontal lobes of the brain above the eye sockets.

- Periaqueductal gray

- The gray matter in the midbrain near the cerebral aqueduct.

- Preoptic region

- A part of the anterior hypothalamus.

- Stria terminalis

- A band of fibers that runs along the top surface of the thalamus.

- Thalamus

- A structure in the midline of the brain located between the midbrain and the cerebral cortex.

- Visual cortex

- The part of the brain that processes visual information, located in the back of the brain.

References

- Anderson, A. K., Christoff, K., Stappen, I., Panitz, D., Ghahremani, D. G., Glover, G., . . . Sobel, N. (2003). Dissociated neural representations of intensity and valence in human olfaction. Nature Neuroscience, 6, 196–202.

- Berkman, E. T., & Lieberman, M. D. (2010). Approaching the bad and avoiding the good: Lateral prefrontal cortical asymmetry distinguishes between action and valence. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 22(9), 1970–1979. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21317

- Berridge, K. C., & Kringelbach, M. L. (2013). Neuroscience of affect: brain mechanisms of pleasure and displeasure. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 23, 294–303. doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2013.01.017

- Berridge, K. C., & Kringelbach, M. L. (2008). Affective neuroscience of pleasure: Reward in humans and animals. Psychopharmacology, 199, 457–480. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1099-6

- Blanchard, D. C., & Blanchard, R. J. (2003). What can animal aggression research tell us about human aggression? Hormones and Behavior, 44, 171–177.

- Farb, N.A.S., Chapman, H. A., & Anderson, A. K. (2013). Emotions: Form follows function. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 23, 393–398. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2013.01.015

- Fox, N. A., & Davidson, R. J. (1986). Taste-elicited changes in facial signs of emotion and the asymmetry of brain electrical activity in human newborns. Neuropsychologia, 24, 417–422.

- Freese, J. L., & Amaral, D. G. (2009). Neuroanatomy of the primate amygdala. In P. J. Whalen & E. A. Phelps (Eds.), The human amygdala (pp. 3–42). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Gable, P. A., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2008). Relative left frontal activation to appetitive stimuli: Considering the role of individual differences. Psychophysiology, 45, 275-278.

- Goldstein, K. (1939). The organism: An holistic approach to biology, derived from pathological data in man. New York, NY: American Book.

- Gottfried, J. A., O’Doherty, J., & Dolan, R. J. (2002). Appetitive and aversive olfactory learning in humans studied using event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of Neuroscience, 22, 10829–10837.

- Gray, J. A. (1987). The psychology of fear and stress (2nd ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Harmon-Jones, E., Harmon-Jones, C., & Price, T. F. (2013). What is approach motivation? Emotion Review, 5, 291–295. doi: 10.1177/1754073913477509

- Heinrichs, M., von Dawans, B., & Domes, G. (2009). Oxytocin, vasopressin, and human social behavior. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 30, 548–557.

- Izard, C. E. (2010). The many meanings/aspects of emotion: Definitions, functions, activation, and regulation. Emotion Review, 2, 363–370. doi: 10.1177/1754073910374661

- LeDoux, J. E. (1996). The emotional brain: The mysterious underpinnings of emotional life. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- LeDoux, J. E., Farb, C. F., Ruggiero, D. A. (1990). Topographic organization of neurons in the acoustic thalamus that project to the amygdala. Journal of Neuroscience, 10, 1043–1054.

- Numan, M., & Insel, T. R. (2003). The neurobiology of parental behavior. New York, NY: SpringerVerlag.

- O’Doherty J. P., Deichmann, R., Critchley, H. D., & Dolan, R. J. (2002). Neural responses during anticipation of a primary taste reward. Neuron, 33, 815–826.

- O’Doherty, J., Kringelbach, M. L., Rolls, E. T., Hornak, J., & Andrews, C. (2001). Abstract reward and punishment representations in the human orbitofrontal cortex. Nature Neuroscience, 4, 95–102.

- O’Doherty, J., Winston, J., Critchley, H., Perrett, D., Burt, D. M., & Dolan, R. J. (2003). Beauty in a smile: The role of medial orbitofrontal cortex in facial attractiveness. Neuropsychologia, 41, 147–155.

- Panksepp, J. (1998). Affective neuroscience: The foundations of human and animal emotions. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Panksepp, J., & Biven, L. (2012). The archaeology of mind: Neuroevolutionary origins of human emotions. New York, NY: Norton.

- Panksepp, J., Normansell, L., Herman, B., Bishop, P., & Crepeau, L. (1988). Neural and neurochemical control of the separation distress call. In J. D. Newman (Ed.), The physiological control of mammalian vocalization (pp. 263–299). New York, NY: Plenum.

- Peterson, C. K., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2012). Anger and testosterone: Evidence that situationally-induced anger relates to situationally-induced testosterone. Emotion, 12, 899–902. doi: 10.1037/a0025300

- Reynolds, S. M., & Berridge, K. C. (2008). Emotional environments retune the valence of appetitive versus fearful functions in nucleus accumbens. Nature Neuroscience, 11, 423–425.

- Reynolds, S. M., & Berridge, K. C. (2002). Positive and negative motivation in nucleus accumbens shell: Bivalent rostrocaudal gradients for GABA-elicited eating, taste “liking”/“disliking” reactions, place preference/avoidance, and fear. Journal of Neuroscience, 22, 7308–7320.

- Reynolds, S. M., & Berridge, K. C. (2001). Fear and feeding in the nucleus accumbens shell: Rostrocaudal segregation of GABA-elicited defensive behavior versus eating behavior. Journal of Neuroscience, 21, 3261–3270.

- Schulkin, J. (1991). Sodium hunger: The search for a salty taste. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Seymour, B., Daw, N., Dayan, P., Singer, T., & Dolan, R. (2007). Differential encoding of losses and gains in the human striatum. Journal of Neuroscience, 27, 4826–4831.

- Stewart, J., De Wit, H., & Eikelboom, R. (1984). Role of unconditioned and conditioned drug effects in the self-administration of opiates and stimulants. Psychological Review, 91, 251-268.

- Wacker, J., Mueller, E. M., Pizzagalli, D. A., Hennig, J., & Stemmler, G. (2013). Dopamine-D2-receptor blockade reverses the association between trait approach motivation and frontal asymmetry in an approach-motivation context. Psychological Science, 24(4), 489–497. doi: 10.1177/0956797612458935

- Whalen, P. J. (1998). Fear, vigilance, and ambiguity: initial neuroimaging studies of the human amygdala. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 7, 177–188.

Authors

Eddie Harmon-JonesEddie Harmon-Jones, Professor of Psychology at The University of New South Wales, Australia, has received early and mid-career awards for his research on affective and social neuroscience from the Society for Psychophysiological Research and the Society of Experimental Social Psychology.

Eddie Harmon-JonesEddie Harmon-Jones, Professor of Psychology at The University of New South Wales, Australia, has received early and mid-career awards for his research on affective and social neuroscience from the Society for Psychophysiological Research and the Society of Experimental Social Psychology. Cindy Harmon-JonesCindy Harmon-Jones is a research associate at The University of New South Wales, in Australia. Her research focuses on emotion and motivation.

Cindy Harmon-JonesCindy Harmon-Jones is a research associate at The University of New South Wales, in Australia. Her research focuses on emotion and motivation.

Creative Commons License

Affective Neuroscience by Eddie Harmon-Jones and Cindy Harmon-Jones is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

Affective Neuroscience by Eddie Harmon-Jones and Cindy Harmon-Jones is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.